Before writing about Sri Lanka, a quick rant about my love‑hate relationship with Mafengwo. I’ve never been a studious type; I’ve always preferred wandering around, and later fell in love with travel. Before each trip I browse many sites for information and eventually settle on Mafengwo for inspiration. It’s been my favorite travel site for years.

What attracts me most is not only the down‑to‑earth travel journals from ordinary people, but also the practical writing tools it offers to those who share their experiences—tools other big sites should learn from.

But in recent years Mafengwo has also become a paradise for show‑offs and clickbait. Travel isn’t about flaunting or ticking boxes; it’s about understanding the world and ourselves. On that, Mafengwo’s gatekeeping is weak. Pages are flooded with so‑called “food” and selfies, which may please some readers but lower the bar and mislead would‑be travelers.

Sri Lanka is a clear example!

Most articles about Sri Lanka are uncritical praise: “English vibe” in Nuwara Eliya, radiant smiles, charming island scenery, “the sapphire of the Indian Ocean.” I was lured by such writing into this unattractive country. Twenty‑four days can’t fully reveal a nation’s culture, but they are enough for a rough feel. If dishonesty or scams happen only occasionally, maybe it’s nothing. But from the moment we entered, we ran into such things almost daily—definitely not a coincidence.

Everyone Likes To Show Pretty Pictures

Even When Ugliness Is Everywhere

The image of Sri Lanka I once had was primitive and exotic, simple and devoutly Buddhist—ornamented elephants carrying noble kings to receive blessings. After 24 days traveling entirely by bus and train, covering 1,200 km and staying in 11 cities, many of those impressions changed. A country with such rich natural resources has fallen behind in civility due to years of war and poverty; more troubling are the pervasive bad behaviors. Scammers and chancers are everywhere; the brighter the smile, the more likely something sly hides behind it. It’s not a lovable country.

Even so, there are flowers blooming amidst trash, sunshine rarely seen back home, endless public beaches, sweet cheap mangoes, and those adorable yet intimidating elephants. There were still a few nice memories.

A family dressed in festival finery

Galle Fort: An old man and his dog at dusk

Arugam Bay: Fishermen revel in their catch

Hikkaduwa Beach: Graceful surfers

Pinnawala: Close encounters at the Elephant Orphanage

Sri Lanka has few truly distinctive natural sights or cultural monuments (unless you count Sigiriya/Lion Rock).

People say Sri Lanka is cheap; it depends what you buy. A plate of fried rice in a restaurant is at least ~25 RMB; bottled water in a supermarket is ~LKR 45 (just over 2 RMB). Cheap? Roughly like Beijing. It feels inexpensive mostly because there’s nothing high‑end to spend on.

Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage

I prefer free‑form travel, often deciding each morning where to sleep at night. I’d heard good things about the Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage, so it became my first stop.

It’s a facility where elephants are kept and cared for by people.

That choice turned out right; our two days in Pinnawala were the happiest and most comfortable in Sri Lanka.

If you’ve seen African elephants on the Kenyan savannah, you probably watched from afar. Here it’s different—giants pass right before you, like mountains rolling in. Standing by a narrow street, hiding behind a utility pole, you hear their heavy footfalls thumping the ground. Massive bodies sway past, shaggy and wet, trunks swinging. You fear a careless bump, and feel both fear and thrill—something you can only grasp in person.

Many people do Pinnawala as a one‑day car trip paired with Sigiriya, spending two rushed hours to watch the elephants bathe—time‑efficient, but not meaningful. Even if you catch them “going home,” you won’t feel the avalanche‑like herds streaming past at arm’s length. We stayed two nights and saw five street parades—thrilling and addictive!

Each morning and afternoon the elephants walk from their compound to the river for two hours of bathing. Mahouts steer the herds below several hotel terraces; you can sip coffee on a balcony and even stroke a shaggy trunk in the fresh sunshine. If you’re traveling with kids, plan two nights—they won’t want to leave.

These big guys are shaggy and wet—touching them feels surprisingly sensual!

Elephants bathing.

In Sri Lanka we learned from several Europeans not to compromise. One morning at our hotel entrance, two locals tried to extort them—likely over a photo‑fee “misunderstanding.” Many Chinese would concede to avoid hassle, which fosters the habit of preying on Chinese: bribes at immigration, padded restaurant bills, etc.

I watched closely. Their approach: first, only one person engaged the hustlers while the others stayed silent; second, they kept repeating two words—“No”—and the agreed price. No third phrase, no yelling, just firm seriousness. In the end, the Europeans won.

We followed that example thereafter, firmly protecting our rights. Justice prevailed.

Several hotels tip the mahouts, who split the herds and bring them to the riverbed below the terraces for bathing.

A calf cuddles with its mother.

After bathing they line up to return, like athletes at a starting line—waiting for the signal, then surging forward.

When tons of flesh roll toward you, fear and excitement make every hair stand on end.

Pinnawala is barely a town, yet crowded with visitors because of the orphanage. The “sights” all revolve around elephants. A 100‑meter street is the daily parade route, lined with souvenir shops.

If you don’t stay inside, a single visit costs LKR 2,000. Bath times are 10:00–12:00 and 14:00–16:00, then they queue to return; some calves or sick elephants come earlier. If you lodge within, you can watch freely.

Two or three hotels sit by the bathing river. Facilities are decent; you can watch from the restaurant. If staying a few days, choose one of these—especially the “green sign” one, which is quiet. The one opposite is chaotic with tour groups on the balcony.

Rack rate for a standard room starts around LKR 8,000 with breakfast, no bargaining; book online only if cheaper. The owner’s been running it for over a decade—nice and professional. Breakfast is poor: one egg and bread with butter, no veggies or fruit. That’s typical across Sri Lanka; don’t be picky.

This is probably the best hotel here—yet even its roofs are made of corrugated sheets.

Guests dine on the terrace daily while watching elephants bathe in the river below.

The only noteworthy shop sells paper products “made from elephant dung”—delicate and fun.

Whether it’s truly made from dung, I’m not sure; later we found locals aren’t big on honesty. I bought a few notebooks as gifts anyway.

Pinnawala was where we first experienced shameless behavior:

** In a fast‑food shop, locals paid little for huge plates of rice with sides, but our single rock‑hard chicken piece cost LKR 300—smiles while fleecing you.

** The next day a buffet without posted prices: we agreed a price, then at checkout they denied it—“only one piece of chicken/fish per person; take two, pay extra”—all with that smiling rogue face.

Sigiriya (near Dambulla)

Our second stop was Sigiriya (Lion Rock), Sri Lanka’s lone world‑class site, touted as one of the “Eight Wonders.” By whom, I don’t know. Frankly: it’s overrated.

Historically, even minor Chinese sites dwarf it; the few murals can’t compare with Dunhuang—Yungang has corners with more to see. Scenery‑wise, many places in China are better. But with so few major relics in Sri Lanka, skipping Sigiriya feels wrong, so we went.

Online it’s listed under Sigiriya, but it’s really a stand‑alone site. Stay in nearby Dambulla, then hire a car or take a tuk‑tuk to Sigiriya. It’s ~6 km; drivers wait 2–3 hours. LKR 2,000 is the going rate.

Dambulla looks big on the map.

This is how we traveled—bags on the engine cover.

Every bus belches choking black smoke. Doors stay open; people hang outside until the driver taps the brake and they vanish inside.

Red ones are state‑run.

Blue‑white ones are private.

All of them smoke!

Routes are clearly marked on both. Private buses cost a bit more; all are in poor condition and run long routes. For Chinese travelers they’re astonishingly cheap—even if conductors overcharge foreigners. Our longest leg of 220 km was only LKR 390 per person.

Unlike China, buses stop constantly to pick up and drop off. Drivers and conductors shout to pack the bus; if you board late, you stand. Timetables exist, but departures often circle the station to recruit passengers. 70–80 km can take over two hours.

At least we met a lovely girl who kept us company along the way.

There are many hotels between Dambulla and Sigiriya that claim “Lion Rock is visible as soon as you look up.” In reality, fields are flat and the rock is tall—you can “see it” from anywhere. Don’t book those online; you’ll regret it!

Sigiriya is one of the few places that charges foreigners—USD 30. Locals pay in Sinhala price tiers. People complain about ticket prices in China; compared to Sri Lanka, China’s are kind.

The panoramic view from the summit is nice. The climb isn’t as brutal as some guides say; one bottle of water is enough. Round‑trip ~2 hours, ~3 hours if you linger for photos. If you’re not into history, time is better spent on a beach.

And tuk‑tuks? They’re these things.

They’re lawless and price‑gouge foreigners. If they open at LKR 300, counter with LKR 100 and walk away—they’ll chase you and settle near that. Locals pay LKR 40–50 for short hops.

Tuk‑tuk drivers swarm foreigners, chattering in fluent or broken English. Polite refusals don’t work; they keep going. Be firm. I usually say “NO!” before they even start—and again before the second sentence. Without a smile. Only then do they leave you alone.

East Coast: Trincomalee

We headed north to Trincomalee—such a ringing name. The bus from Dambulla costs LKR 147 per person, stopping constantly. The “city center” is just a fork and a few streets. Supposedly the East’s largest city and a former LTTE naval base, but smaller than many small towns back home.

In Trincomalee proper there are no buildings over three floors. Roadside shops are shabby; traffic is chaotic.

At the market we found primitive scales used by many vendors: a simple balance with 1‑kg and 0.5‑kg weights. Accuracy is… questionable.

If you end up in Trincomalee, find a beach hotel and settle in fast.

Resort hotels are north along the coast, not downtown—20 km of sand dotted with properties. In low season they’re empty. Luckily we didn’t book online: walk‑in rates were far cheaper and negotiable. From the bus station, head north 5–6 km for clusters of private hotels. We shouldered our packs and inspected one by one—many looked nothing like their online photos. Most felt like budget family inns. We checked at least a dozen before picking one.

Gentle, fine sand; blue water; small waves; fresh air; few tourists—that’s Trincomalee’s beach.

Photos show the prettiest angles, but the beach is strewn with trash—bottles, nets, plastic bags. Even with daily cleaning, each hotel only tidies its own frontage.

If you’re not picky about the broader environment, you can still find decent beach stays.

Our choice wasn’t large—no rows of standard rooms—but the seaside bungalows where you “look up and see the waves” were irresistible, and the vibe was great. The Sri Lankan lads were warm and sunny; we stayed four nights straight.

Four nights were LKR 16,000 without breakfast—online rates were nearly double.

Sri Lankan beaches are similar: yellow sand, big waves, lots of trash—popular or not. The “invincible beaches” in many write‑ups are largely wishful thinking.

When idle, the hotel lads play cricket on the sand—with real flair.

North of Trincomalee are many hotels, so the street has several eateries catering to foreign tastes. Cheaper than hotel dining and at least they post prices—plus a 10% service charge.

A recommendation—not a “delicacy”, but the only Sri Lankan dish I liked: seafood fried noodles. Decent, and we ordered it in several places.

One unreliability in Sri Lankan dining: the same hotel, same cook, two plates of the same noodles can taste completely different.

Salad—something we ordered occasionally, since other veggies were often inedible.

Tropical fruit is abundant and cheap. Fresh coconuts cost LKR 40–50—chop and drink. Large mangoes are LKR 100 for 3–4. Fresh juices—papaya, mango, pineapple—are pure and inexpensive, so there’s no incentive to dilute.

In Trincomalee we continued to encounter shameless tricks:

** A street eatery making Indian paratha quoted LKR 30 each. The owner’s warm smile and other patrons’ praise were convincing. We ordered one paratha and two sides; he served a “triangular” fold—tasty, so we ordered another. At checkout the bill exploded. Why so much? “You had four parathas.” We said two; “No, I served four.” Ah—the triangles were double portions. And the price? “Actually LKR 50 each.” The earlier quote evaporated along with his smile. Whatever—consider it charity to bandits; the total was only ~20 RMB.

Such incidents are common in Sri Lanka; not having two a day is lucky. As for “warm hospitality”—maybe we visited a different Sri Lanka.

Trincomalee

Humanity: 4 (many deceitful merchants; few smiles—perhaps due to long war)

Environment: 4 (trash everywhere)

Air: 9 (fresh, except heavy exhaust when buses pass downtown)

Fun: 4 (below average, and that’s generous)

Overall: 1 (if you have lots of time and want to see how backward it can be, come)

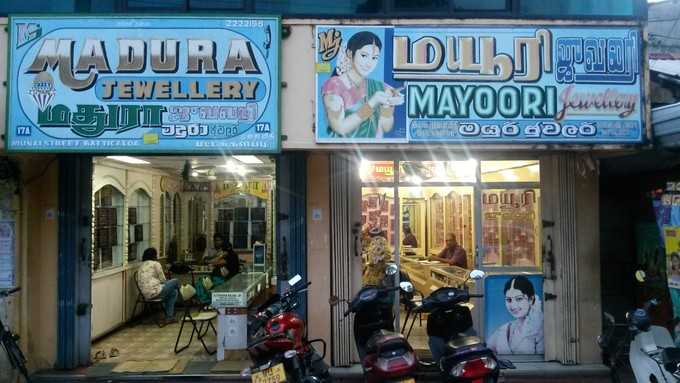

Batticaloa

We continued south along the coast from Trincomalee. It felt slightly “richer”—buildings even had three floors! The city looked more orderly. The beach is far from town though, so we just found a place for the night and moved on next morning.

This is the busiest street in town. Urban scale and infrastructure lag at least 50 years behind small Chinese cities.

At night only a few lit buildings break the darkness.

If Sri Lanka leaves anything deeply, it’s the children—bright, innocent smiles; friendly greetings even from the shy ones. Unlike many kids back home who carry heavy caution.

One wonders how many will grow into chancers and cheats.

Arugam Bay: East Coast Surf Spot

We continued south toward Arugam Bay. The bus goes only to Pottuvil; then take a tuk‑tuk 3–4 km to Arugam. Drivers open at LKR 300–500; counter with LKR 100—soon you’ll pay LKR 100 daily. Arugam Bay is just a stretch of beach near Pottuvil, with hotels, guesthouses, and eateries clustered more tightly than in Trincomalee. The vibe is like budget seaside inns. Each hotel differs; walk the beach and choose—don’t pre‑book.

Enough criticism—some positives:

Sri Lanka protects natural environments far better than many places. Wetlands are everywhere, some fenced; there are no sea cages, few large farms, hardly any factories. The mangroves that are “scenic spots” in Hainan are commonplace here, especially along the East Coast.

Another admirable trait: no one eats the wildlife. Waterbirds fill the sky; creatures roam rice fields; monkeys are everywhere—and left alone.

Arugam Bay still doesn’t offer much to “do.” We checked 7–8 places and chose a hotel with rooms facing the beach and large balconies—days of sea breeze and nights of wave sounds.

This beach is famous for big waves—great for surfing. The sand is fine and the water clear, but the seabed slopes steeply and waves are large—unsuitable for weak swimmers or children. Winter is low season; March–August is peak surf, with 7–8 meter waves—thrilling to watch.

Shallow reefs protrude near the resort.

At dawn beneath crimson skies, fishermen return. As light grows, the beach bustles—sorting fish, sharing catch, joy on faces. It’s a playground for photographers: departures, net‑mending, net‑pulling, picking fish.

Crows line up waiting for discarded small fish.

The silhouette of a Muslim villager

In Arugam Bay we met more shamelessness:

** The hotel owner took our payment the night before to “save morning hassle” and agreed breakfast at 7:00. Next morning he said we were too early, the cook couldn’t get up—no breakfast.

Utterly rogue. We’d asked before check‑in—any meal time was fine, even 6:00. Speechless.

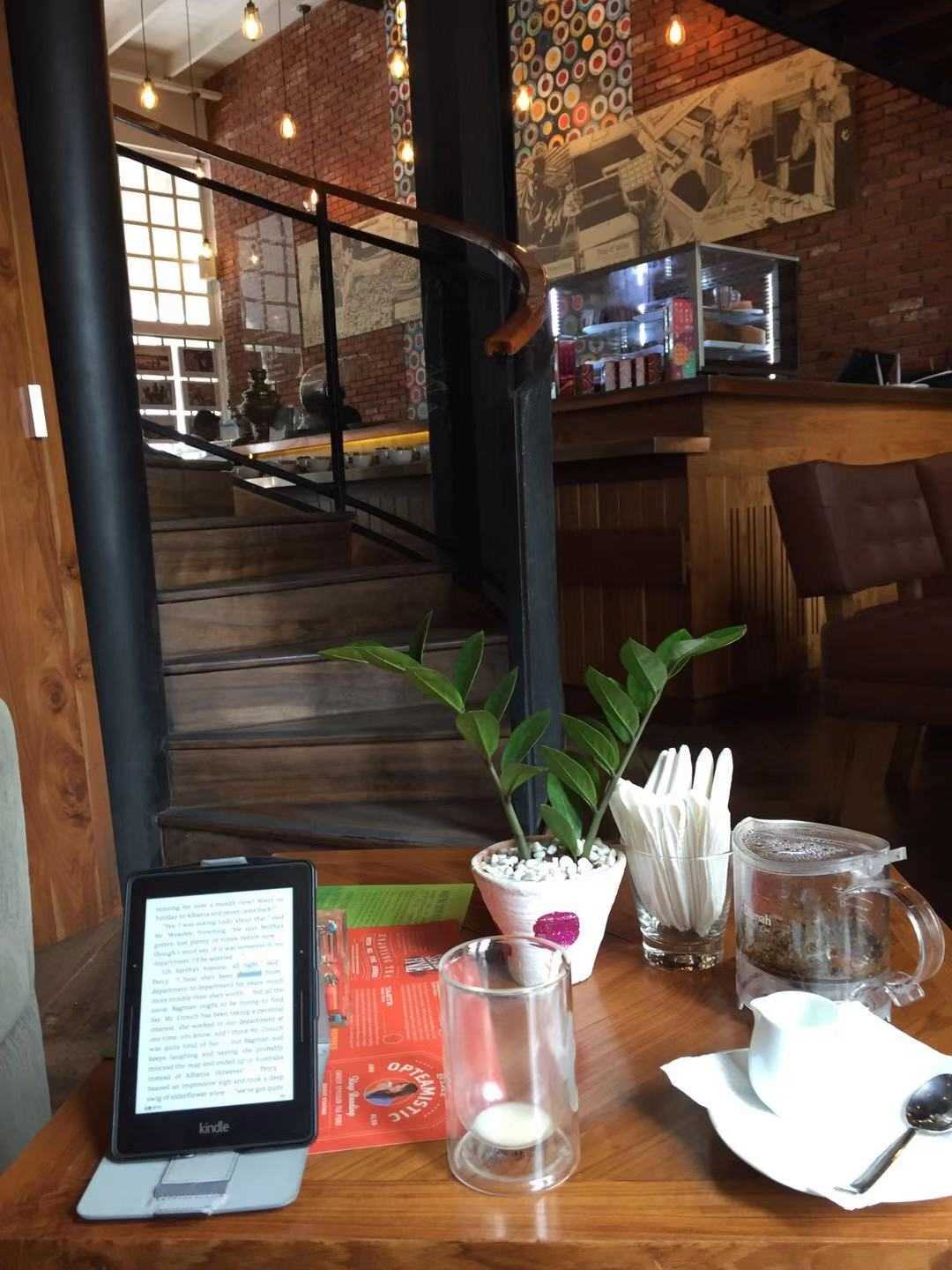

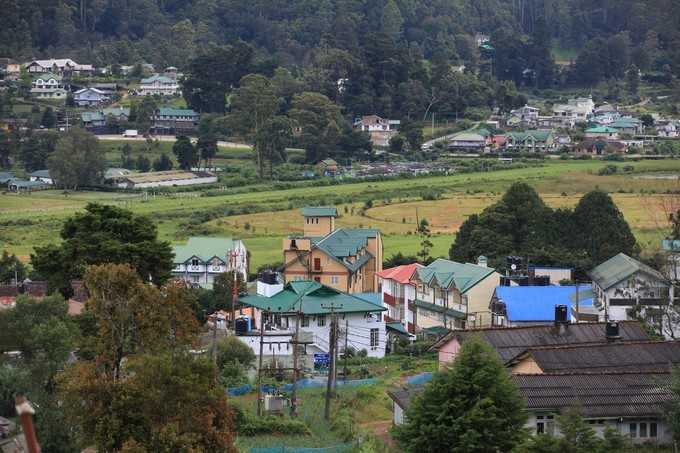

Nuwara Eliya: A City Overhyped by Writers

We climbed from Arugam Bay to Nuwara Eliya via three transfers, 7.5 hours. Narrow roads under repair—slow going; colder as we ascended. Aside from trash and chaotic housing, the scenery did improve. Nuwara Eliya sits above 1,000 m; daytime around 20°C—cold: long pants and jacket by day, blankets at night; when the sun appears, it still scorches.

Guides praise Nuwara Eliya as “English style.” After visiting, I disagree. Have they even been to the UK? Perhaps not even Dubai.

We rested here four days, explored every corner: trash everywhere, haphazard buildings, disordered streets, heavy exhaust—nothing like England. Of the places we visited, this was among the worst.

Tuk‑tuk drivers hustle everywhere, pitching hotels and “deals.” Smile‑y strangers greet you and chat; say more than three words and suddenly everyone “has a relative in China studying at Peking University.” Keep talking and you’re in a trap. We fell for one small scam before learning the pattern.

These two count as “major sights” in town.

That’s it!

And that—apparently any spire counts as “English vibe.”

A chaotic station.

Sewage everywhere.

Hotels crowd the hillside by the lake, competing to build taller, blocking views—just like back home. Styles clash; colors are as gaudy as possible; the slope looks chaotic. Add sagging power lines and solar tanks—nothing close to “English.” If the British saw this, they’d sue.

This photo from our lodge tries to avoid broken bricks on corrugated asbestos roofs below.

See the roofs below? Mostly asbestos sheets and metal panels.

Worse than all that is the exhaust. Streets are full of cars belching black fumes—acrid stench. Escaping smog to “drink exhaust” here?

Many vehicles are near‑scrap, so smoke is no surprise; more alarming is new Japanese and German cars also smoking—likely fuel quality. Every trip downhill for food required a covered nose; we returned with oily faces.

This is the “English town” so heavily praised online.

Fruit in Sri Lanka is cheap—even foreigner prices are attractive. Street fruit shops are many; most are tree‑ripened and fragrant. When meals disappoint, eat more fruit. Large mangoes are LKR 100 for 4—though I’m sick of mangoes now.

In Nuwara Eliya we met more roguery:

** Locals are served water automatically; foreigners are asked what they’ll drink, and if it’s not a paid beverage—no water. You sit ignored while locals get refills. We saw this countless times.

Nuwara Eliya

Humanity: 2

Environment: 3

Air: 4

Fun: 1

Overall: 1 (if you’ve never visited a county‑level town at home and have spare cash, come here)

To be fair, Sri Lankans are kinder to their own than many Chinese. They scam foreigners relentlessly, but treat their own decently. We Chinese too often mistreat our own while bowing to foreigners.

Galle Fort

We endured a long haul from Nuwara Eliya to the southern coastal city of Galle—Sri Lanka’s second must‑see. The west coast is generally more developed than the east; Galle is a true city—it even has KFC! We ate twice and finally felt full.

The long‑distance bus station and train station sit together; opposite is Galle Fort—walk a few hundred meters through the gate and you’re in another world. If Sri Lanka has any hint of Europe, it’s here. Stay inside the fort; forget the dirty, chaotic new town outside. If someone enthusiastically offers to “lead you to the fort,” ignore them—you’ll end up at a random guesthouse or the wrong direction.

Through this gate and you enter the fort.

The only reasonably tidy streets we saw in Sri Lanka

Blooming flowers—name unknown.

Galle Fort was built by the Portuguese in 1505. In sunset glow its ruined walls shine over green lawns; anything living becomes the scene’s protagonist.

Sunrise is just as colorful.

These views belong to no one rich alone.

Residents strolling at dawn.

Muslims are prominent in this city; black abayas and white robes are everywhere.

Boats heading out to fish.

An elder collecting shells at dawn.

The lighthouse and the white mosque—icons of Galle.

Masters of the ruined fort—crows.

This is the only truly stroll‑worthy small street we found in Sri Lanka—quiet, cute, and refined. Guesthouses are plentiful; in low season, walk‑in rates are almost half of online prices. There are proper large hotels too for the picky. Strolling within the fort you can even sip a rich coffee at a cafe run by Westerners.

From our hotel balcony we could see the ramparts and the sea.

On clear days you may even meet families shooting wedding photos.

In Galle we met more roguery:

** Fresh off the bus station, a smiling driver whisked us into his tuk‑tuk. We didn’t haggle and paid LKR 300 to “the fort”—it should be LKR 100. He sped us to the new town instead, then feigned ignorance. At least we found KFC and ate well.

** In a restaurant, despite confirming prices for each item, the bill still ballooned—pure bullying, with locals chiming in. Not isolated; it felt cultural—deplorable.

** At the bus station, I ordered the same as locals and paid the same. Then I asked for one more—and the price went up.

** Outside a beautiful school, we stood on steps photographing a big bird. A Honda CR‑V honked incessantly for us to move so she could mount the curb to drop off a child. Such “quality”—yet mother and daughter were well‑dressed.

This is the most “advanced” city in Sri Lanka. If you meet only one rogue in a day, congratulations—you’ve won a prize.

Some might say, “We met no scams in Sri Lanka.” Then perhaps we visited different countries.

Galle

Humanity: 6 (street merchants sell 1‑liter water for absurd prices, among other tricks)

Environment: 8 (the new town is a mess)

Air: 8 (same reason)

Fun: 9 (sunsets and sunrises are magnificent)

Overall: 9 (European flavor—still far from ‘English’)

As for food, Sri Lanka eats the same few things nationwide.

These are curry‑filled, deep‑fried snacks—mostly mashed potato, often with half an egg inside.

I call these “little triangles”: mashed potato filling with a bit of egg, beef, or fish—shaped into triangles and griddled.

This one is similar—just a different shape. They’re cheap and the only food vaguely like Chinese snacks; those who can’t handle Sri Lankan fare survive on these.

This one resembles the first but with chicken inside.

This is like Indian paratha—thin and tasty.

This is like a pancake; locals tear it up and dip it in curry gravy.

We ate these for 24 days. Apart from hygiene they’re quite tasty; I didn’t get tired of them. I watched them being prepared—flies everywhere. On the road, you make do.

This last is like “chopped flatbread” on a hot plate—the loud clacking sound in the street. It’s terribly bland.

Snacks are cheap and tasty, but beware of being ripped off. Ask prices first—usually LKR 30–40 nationwide. If it’s more, something’s off. State how many you’ll eat, or checkout becomes LKR 50 each. The grifter’s smile turns fast. Best to pay per piece and avoid trouble.

A Word on “Sri Lankan Cuisine”

Frankly, there’s little “cuisine” to speak of. Early on we followed guidebook recommendations and ate at two touted places—infuriating for a food‑centric Chinese traveler. Whether seafood or “Sri Lankan flavors,” most dishes are very average. Don’t compare them to Fujian/Cantonese/Jiangnan home‑style cooking; they’re closer to the worst Beijing duck or bland wontons. Better to rely on cheap street snacks to survive.

Hikkaduwa: West Coast Beach

After so many beaches, Hikkaduwa is Sri Lanka’s undisputed No. 1 (just don’t compare it to Hawaii or Miami). The sand color is beautiful and wide; snorkeling is decent—clear, emerald water.

Most guides recommend Mirissa in the south, but one mentioned Hikkaduwa; coming here was wise.

Waves are still sizable, but the seabed is shallow for hundreds of meters—great for surfing practice; even lying on a board to ride waves is fun.

It’s not a fenced “scenic area”; the beach is public, lined with hotels and restaurants. Lounge on hotel sun beds and enjoy a quiet afternoon.

We were lucky to spot two giant sea turtles near shore and even hug them (locals say they frequently approach visitors for seaweed). We didn’t bring cameras on that walk.

Near town there’s a beach with a convenient coral reef—no long trip needed. With a mask you’ll see plenty of fish. Not Sipadan or the Great Barrier Reef, but enough—schools right in front of you.

Three Norwegian girls: eat, sunbathe, eat, read—never saw them get in the water. Hung out with us for three days.

There are tons of places to eat in Hikkaduwa, as most visitors are Westerners. We didn’t see Chinese in three days (seems most stick to Mirissa). There were Japanese and Koreans. Plenty of restaurants—no dining worries. Basic guesthouses don’t offer half‑board; only starred hotels do. We stayed at Coral Sands on HB (breakfast and dinner)—good food.

Fresh juices in hotels are uniformly good—pure flavor; perhaps additives cost more than fruit.

Thanks to the one article that recommended Hikkaduwa—far better than Mirissa; glad we skipped Mirissa. If you want whales and dolphins, go to Mirissa; from Hikkaduwa it’s far—you’ll need an early start to board there.

Hikkaduwa

Humanity: 7 (aside from pesky tuk‑tuks, few truly bad encounters)

Environment: 9 (streets messy—that’s Sri Lanka’s norm)

Air: 10

Fun: 9 (surfing, absolutely!)

Overall: 9 (sun, sand, sea turtles, fish, and great‑value hotels)

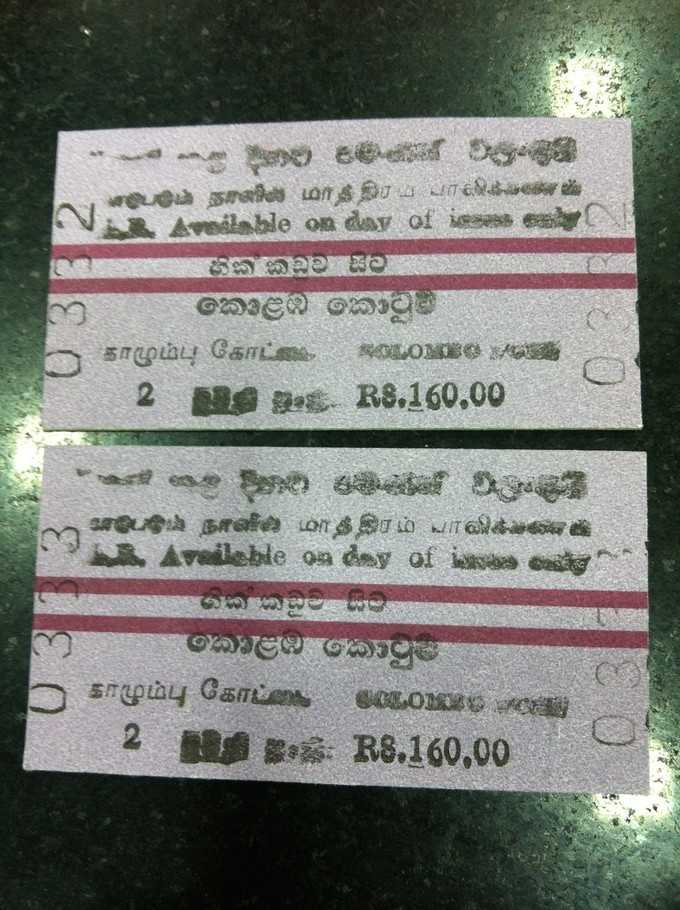

Colombo: Head Home

Our flight was after midnight, so we still spent the morning with the sea. In the afternoon we showered, grabbed our bags, took a tuk‑tuk, switched to train, then bus, and rushed to the airport—ending this vexing Sri Lanka trip.

This is the “seaside train” experience; tickets are old‑school cardboard.

Trains are packed, no reserved seats; you mostly stand. Locals sit at the doorways. Even in that crush, vendors weave through with big tubs—wild.

Why is the train from the fort to the capital hyped so much? Aside from a short seaside stretch, it’s just a commuter train like in small towns back home.

After Sri Lanka, I no longer trust many online articles 100%. To find truly useful travelogues you need sharp eyes.

Colombo—the only photo worth keeping: the final streak of sunset was gorgeous.

In summary: across countries we’ve visited—developed or poor Southeast Asian ones—we usually feel great and leave reluctantly; we even liked Kenya. Only in Sri Lanka did we grow tired after ten days, ready to go home. Though a Buddhist country, locals seemed to have lost simple warmth, without the high civic quality of developed nations. Trash‑filled streets, chaotic cities, cars spewing choking smoke—frustrating. Compared to Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore, Sri Lanka falls far short.

Finally, remember this face: such smiles are everywhere—radiant, seemingly honest and warm, with clear eyes.

This man is devout, performs daily rituals, helps his wife clean the yard—spotless and orderly.

He’s clearly well‑educated, speaks fluent English, crisp shirt, polished shoes. Loving with his wife, one son and one daughter, strict with parenting—honestly better at educating children than many Chinese. I watched their nightly rituals—sincere, not for show—focused less on asking blessings than on love and communication between spouses, gratitude to mother for bearing and father for raising, mutual help among siblings. It was moving. So when we repeatedly found our backpack disturbed, we refused to suspect theft. We had one moment of doubt, then dismissed it—suspecting such a family felt sinful. Only on departure did we find some rupees missing.

It was a small amount in RMB—laughably little, no impact on the trip—but an unforgettable lesson. Faith doesn’t change behavior; faces like his appear often, and behind them can be greed.

I believe his love for his wife, parenting ideals, and respect for the Buddha are genuine—and so was the ugly greed.