Lion Country on the Indian Ocean

— Sri Lanka, 8‑day trip —

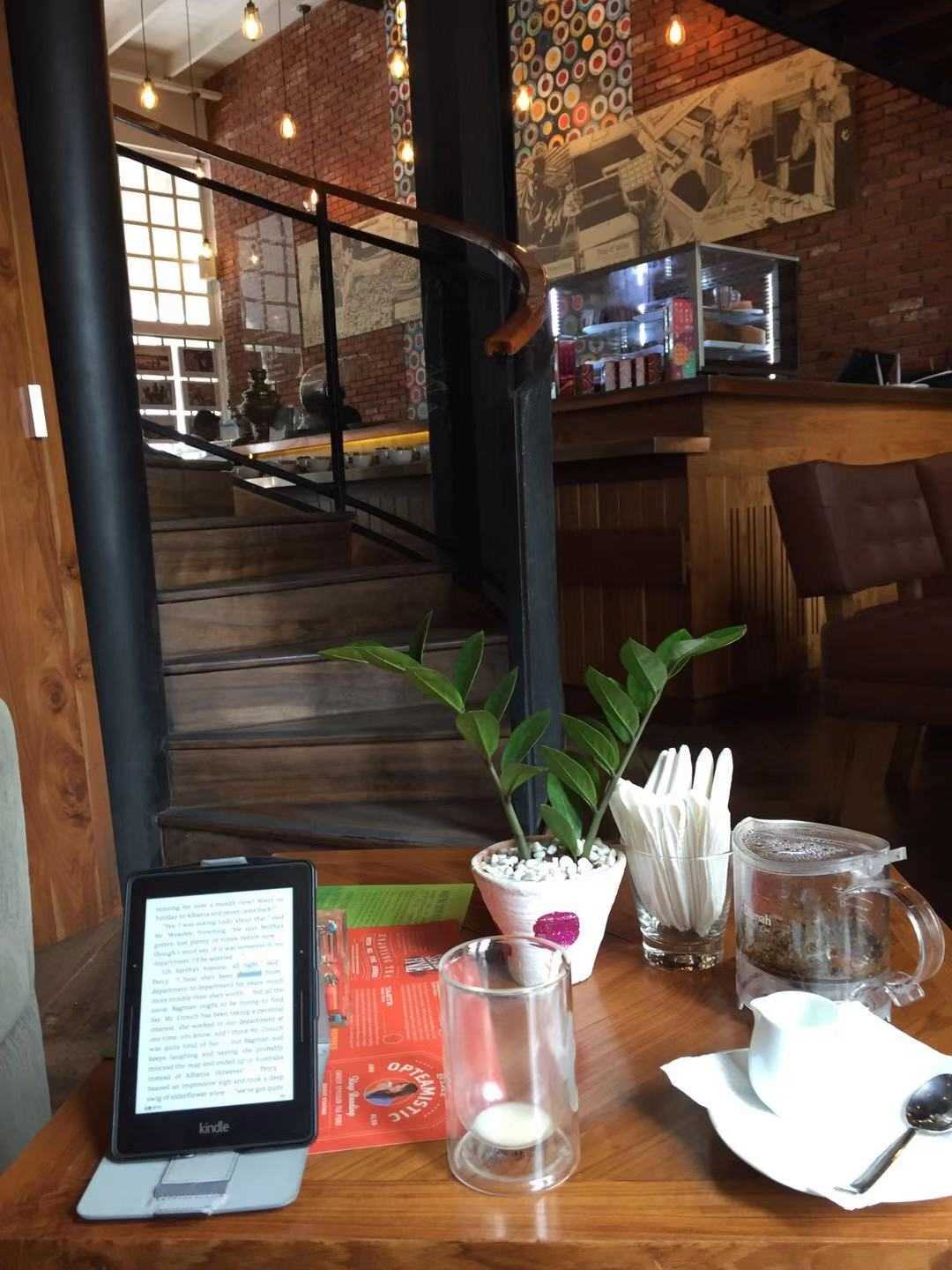

September 9–16, 2016. Sri Lanka had been on my mind ever since I saw blue beaches and the “Spirited Away”‑style seaside train—I couldn’t resist putting it on the schedule. This time I could take my mom abroad; since she traveled solo, she paid a single‑room supplement of 3,000 RMB. Expensive, but it suggested comfortable stays—which proved true. From Kunming you can fly direct to Colombo, very convenient. Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, formerly Ceylon, is a tropical island nation in the Indian Ocean and a member of the Commonwealth. In ancient Chinese it was called the Lion Country or Singhala. Sri Lanka has 9 provinces and 25 districts: Western, Central, Southern, North Western, Northern, North Central, Eastern, Uva, and Sabaragamuwa. It’s multi‑ethnic: Sinhalese ~74.9%, Tamil ~15.4%, Moor (Muslim) ~9.2%, others ~0.5%. Area: 65,610 km². The economy is agriculture‑based; the most important export is Ceylon tea—one of the world’s four major tea producers—so the economy is tied to tea yields. Growth has accelerated during liberalization. Sri Lanka’s big advantages are minerals and geography; it’s rich in gemstones—among the top five producers—and known as the “Island of Gems.” Annual gemstone exports reach ~USD 500 million, especially rubies, sapphires, and cat’s‑eye. It’s called the “Kingdom of Gems” and the “Pearl of the Indian Ocean”; Marco Polo praised it as the most beautiful island. National symbols: water lily (flower), Bodhi tree, cat’s‑eye (stone), and the Sri Lankan junglefowl (bird). I ate the best avocado of my life here—previously I found avocados bland unless mixed with yogurt or milk; the flavor here was unforgettable: rich and delicious.

Saturday, Sept 10: after 4.5 hours we arrived in Colombo at 07:53 Beijing time (05:30 local). After queuing for the restroom, at 08:20 we queued for immigration—crowded but efficient. Phones switched automatically to 06:19 local (08:47 Beijing). Dawn was just breaking as our group finished procedures and regrouped. Outside the terminal were currency exchange counters—about CNY 1 ≈ LKR 20. Most airport staff were men in navy uniforms, with darker complexions.

Our first stop was the Negombo Fish Market, bustling in the morning when boats that left at dawn return—perfect timing. Negombo is a western port city on the north shore of Negombo Lagoon, 30 km north of Colombo, home to Sri Lanka’s second‑largest fish market, rich in prawns and crabs, with remnants of 17th‑century Dutch architecture from Portuguese and British colonial times. We had breakfast at a seaside restaurant, then played and took photos along the beach—blue sea and sky put us in a great mood. Negombo is a fishing village; at the shore we saw many boats just back. Each arrival draws crowds to haul boats, pull nets, unload fish—grand scenes. Fishermen beamed at their harvest. In the market, the dazzling variety of marine fish widened our horizons; many species we’d never seen, some enormous. Seeing all that, we decided to eat fish often in Sri Lanka—every meal if possible. Day one ended with a stroll along the Indian Ocean, feeling life was beautiful.

Leaving Negombo we visited St. James Church. A flock of crows gathered at the entrance. Back home crows often symbolize bad omens, and it’s hard to imagine them perching by your hands like pets, expectantly waiting to be fed. In Ceylon, though, crows coexist harmoniously with people—and many even regard them as sacred birds.

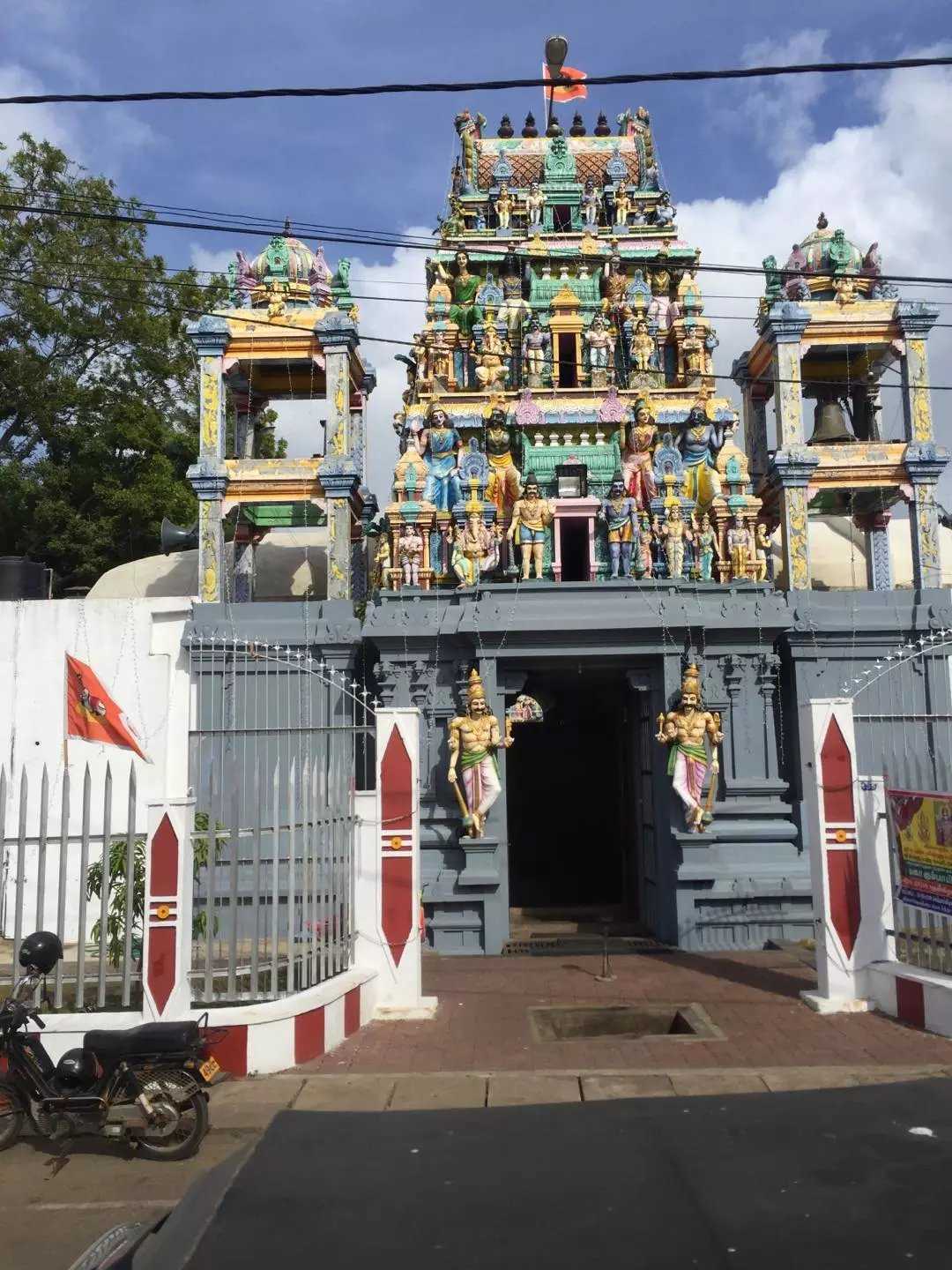

We visited a colorful Hindu temple—a glimpse of Sri Lanka’s most down‑to‑earth side; when we arrived, it was under repair. The old and new temples stand side by side on Sea Street, dedicated to Murugan, the warrior son of Shiva. Entrances are adorned with numerous finely crafted Hindu deities; above the central gate six green dragons support the lintel. Beside them is a Ganesh temple. With basic understanding of Hinduism you gain more from the visit: outwardly it has countless deities, yet many devotees primarily worship one supreme being. The three principal deities are Brahma (creator), Vishnu (preserver, protector), and Shiva (destroyer, often symbolized by the lingam, appearing in many forms). Hindu society is structured by caste with Brahmins at the top; doctrine emphasizes karma and rebirth, ritual and asceticism, and reverence for the Vedas.

We then drove into Colombo to see the city. As Sri Lanka’s largest city, it may feel noisy to Chinese visitors, but for travelers there are colonial‑era buildings, a clock tower, the national museum, and galleries worth a look. First stop: the Bandaranaike Memorial International Conference Hall (BMICH), sometimes called Colombo’s “White House,” built with Chinese aid; it’s not open to the public. Opposite is Viharamahadevi Park and the City Hall complex. In central Colombo, the BMICH is grand and iconic: a 16,000‑square‑foot hall, 400 telephone lines, and a new library. The octagonal plan features an outer colonnade of 48 white marble columns, deep eaves, and lattice walls—light and tropical in character. Built in the 1960s–70s as a gift from China (decision in 1964, completed May 1973), it has served Sri Lankan public life for over 30 years, akin to China’s Great Hall of the People and hailed as a symbol of China–Sri Lanka friendship. Nearby stands the Chinese Embassy—two buildings mirroring each other, symbolizing close ties. The skyline isn’t very tall, though new high‑rises are being constructed—our guide said many are Chinese‑funded. During President Xi and Peng’s visit last year, they also supported a grand theater reminiscent of Beijing’s Bird’s Nest.

Next: Independence Square, east of the University of Colombo, an iconic cultural plaza where the independence ceremony was held on February 4, 1948. From here you can glimpse the white City Hall and see flags flying to the west. Many young people rest and read here—a pleasant, quiet spot. On the memorial hall’s beams and columns you’ll see carvings of elephants, lions, and scenes from Sri Lankan Buddhist history. Art students practice sketching; around the hall are 60 stone lions symbolizing the Sinhalese, each representing a king in the Kandyan style. The central Independence Memorial Hall echoes the royal audience hall of the Kandyan era. Fountains play at night; green lawns surround the monument, framed by stone lions. On the back stands the statue of D. S. Senanayake, Sri Lanka’s first prime minister.

Sri Lanka is a Buddhist country where monks are deeply respected. When speaking with monks, people keep their head slightly lower than the monk’s, whether standing or sitting, and never pass items with the left hand. On buses, ordinary passengers board from the rear, monks from the front, with reserved seats. Note that nodding and shaking your head mean the opposite of in China—nodding is “no,” shaking is “yes.” Sri Lankans eat with the thumb, index, and middle fingers of the right hand; gifts shouldn’t be flowers, and both dining and receiving gifts are done with the right hand. Besides the rule “no food after noon,” Buddhist ascetics avoid entertainment venues, cycling, running fast, riding carts pulled by female animals, wearing watches, and they go barefoot in temples. Sri Lankans greet newcomers with handshakes or palms pressed together at the face—the latter is most formal.

That night we checked into the Mount Lavinia Hotel facing the beach—powder‑fine sand and a boundless sea, a lovely view. Coconut palms line the terrace. At dusk we saw many people swimming and playing on distant sands. It must have been an auspicious day—we arrived to a family dressed for a wedding; after we went out and returned, another wedding was underway there. Attire was elegant and colorful, especially the women. Sinhalese wedding customs are unique: after engagement and setting a date, rings are exchanged. On the wedding day, the bride’s younger brother washes the groom’s feet, they tie a “knot of unity,” and break a coconut. The rites conclude when the bride, on the wedding dais, wears the flower cloth around her waist and a fish‑shaped hairpin from the groom. In the central highlands, polyandry still exists. Mount Lavinia Hotel—beautiful from every angle. Sitting quietly on the balcony with waves crashing and palms shading—“facing the sea, with spring’s flowers” feels too mild to describe it…

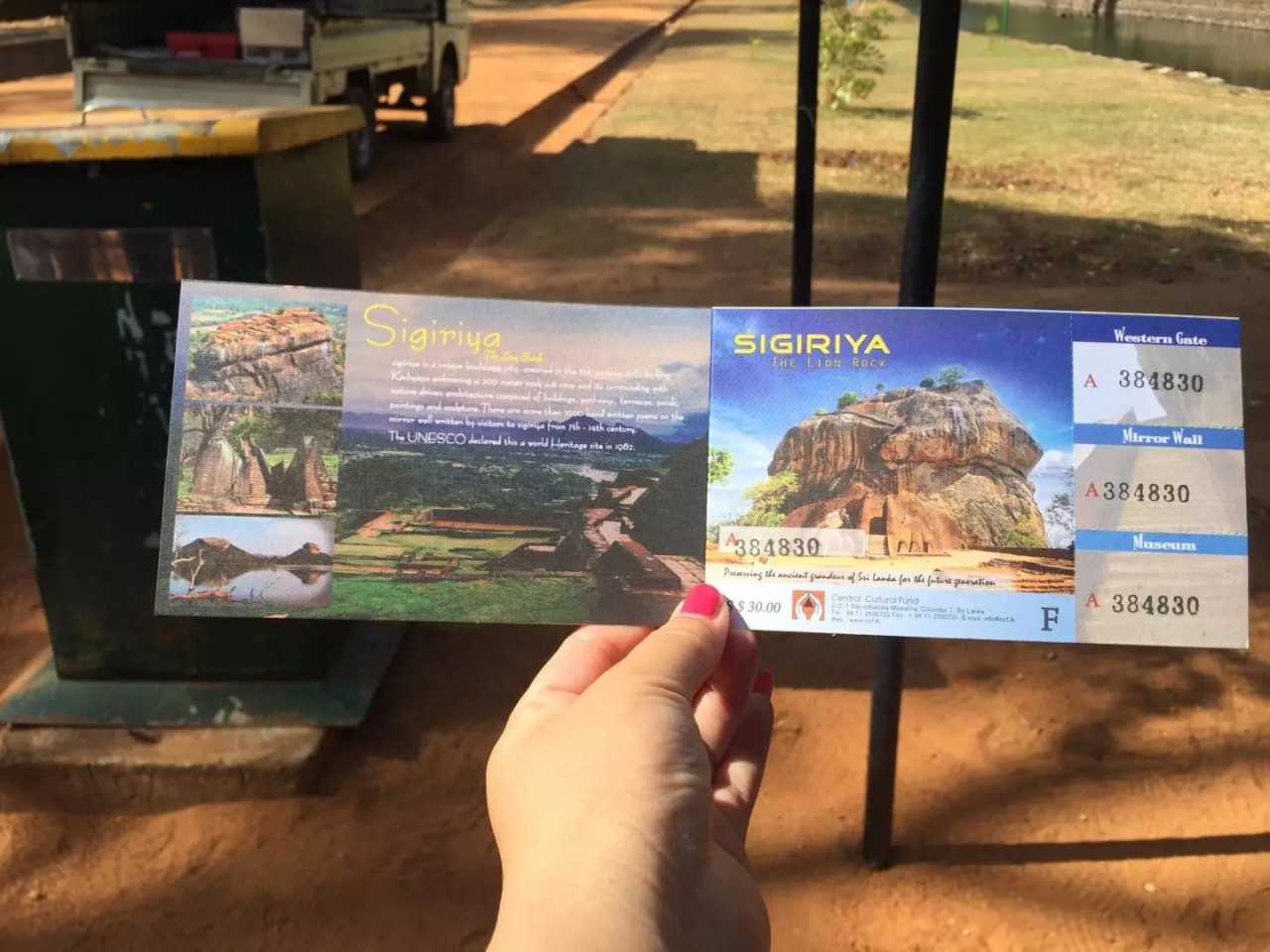

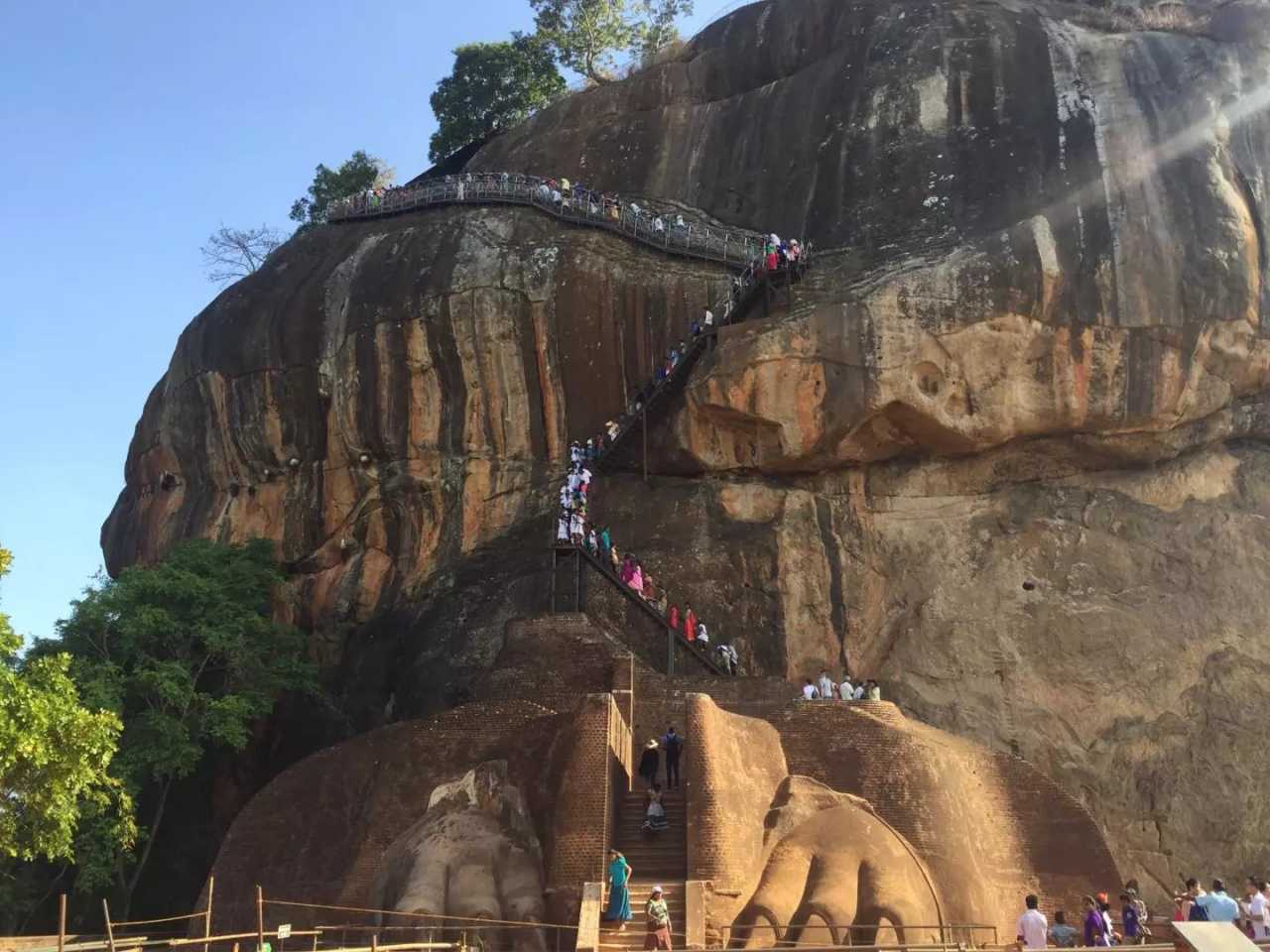

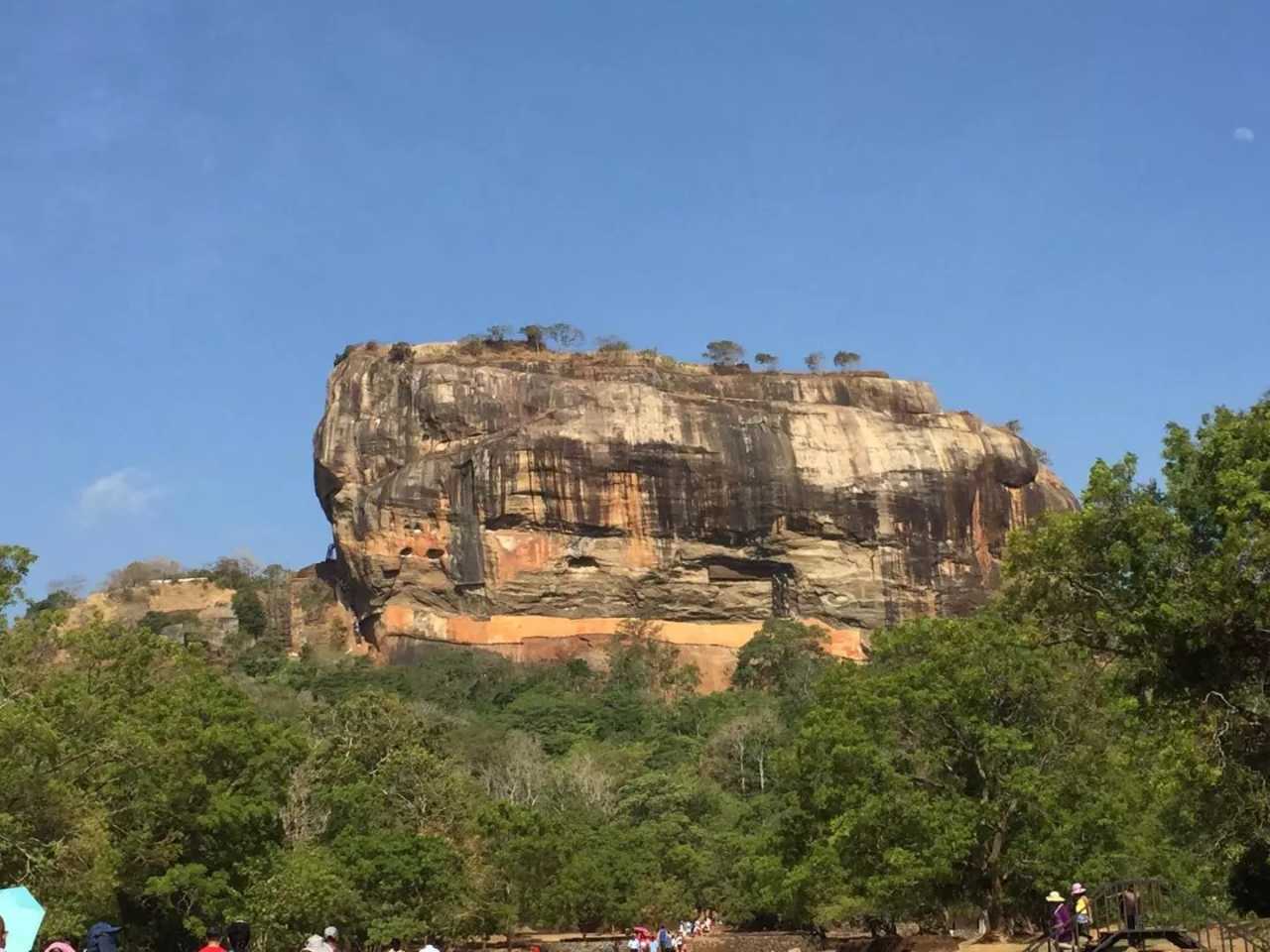

Sunday, Sept 11: after breakfast we drove to Sigiriya to visit Lion Rock. Its origin has a story: King Kashyapa I seized the throne in 477 CE after killing his father. His half‑brother Moggallana fled to India. To avoid retaliation, Kashyapa chose an isolated monolith ~70 km from the capital—Sigiriya—to build a palace and fortress on a rock that was easy to defend. Lion Rock rises abruptly from the plain to ~370 m. Legend says Kashyapa built his citadel here; corridors and stairs made of lime, brick, and clay extend from the mouth of a colossal lion, allowing people to ascend to the ancient city. Sigiriya is a jewel of Sri Lankan ancient culture. After nearly a decade of construction, Kashyapa created a sky palace of ~20,000 m² atop Lion Rock—both pleasure palace and stronghold. Below the rock lies the royal garden, said to be among the world’s oldest landscaped gardens, divided into water gardens, boulder gardens, and terrace gardens. Walking the site, the “city” feels modest, but from above it’s expansive: a square moat encircles Lion Rock; the east and west city areas stretch ~3 km east–west and ~1 km north–south, with two moats and three walls. A quick visit takes < 2 hours; a leisurely one takes half a day. At the base are garden ruins—pools and foundations outlining former buildings. We climbed steep stairs among crowds, viewed frescoes and palace remnants, descended around 18:00, dined, and checked into our hotel…

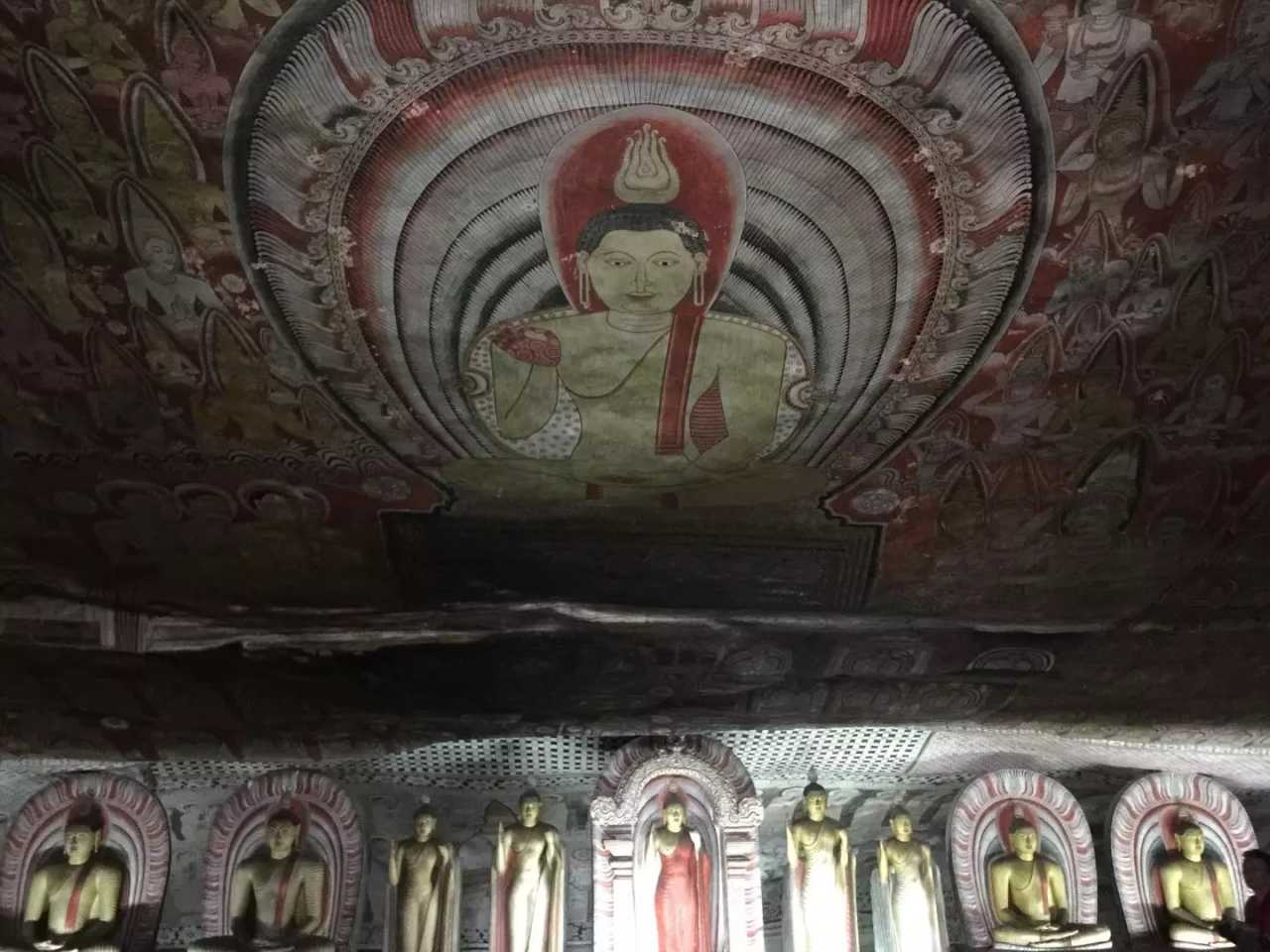

Monday, Sept 12: we set out at 10:00 for the Dambulla Cave Temple. In Buddhist temples you must remove shoes and hats, keep shoulders and knees covered, and never step on, straddle, or climb over Buddha images. There is a shoe deposit at the gate—25 LKR per pair, no change given. Dambulla sits in central Sri Lanka, 149 km northeast of Colombo and about 60 km north of Kandy. The cave temple, founded in the 1st century BCE, is a major pilgrimage site, carved into a giant rock south of Dambulla town, with over 2,000 years of history. It is Sri Lanka’s best‑preserved cave temple complex, famed for murals and statues. The complex comprises five shrines. Cave 1 houses a 14‑meter reclining Buddha with Ananda at his feet and an image of Vishnu above the head—hence it is called the “Devaraja Lena.” Cave 2, the largest, contains 16 standing Buddhas, 40 seated Buddhas, two Hindu deities (Vishnu and Saman), and statues of kings Vattagamani and Nissanka Malla; a small stupa stands within. A spring in the cave strangely appears to flow upward along a fissure and drips day and night—believers call it sacred water. Cave 3, the “Maha Alut Viharaya,” features 17th‑century Kandyan‑style paintings and a statue of King Kirti Sri Rajasinha (1747–1782), who revived Buddhism. Cave 4 is smaller, with a single seated Buddha; its stupa was once looted. Cave 5 was a storeroom and now holds a giant reclining Buddha with many Hindu deities beside him. The murals are extraordinary—geometric patterns on the ceilings and richly colored walls—most in excellent condition.

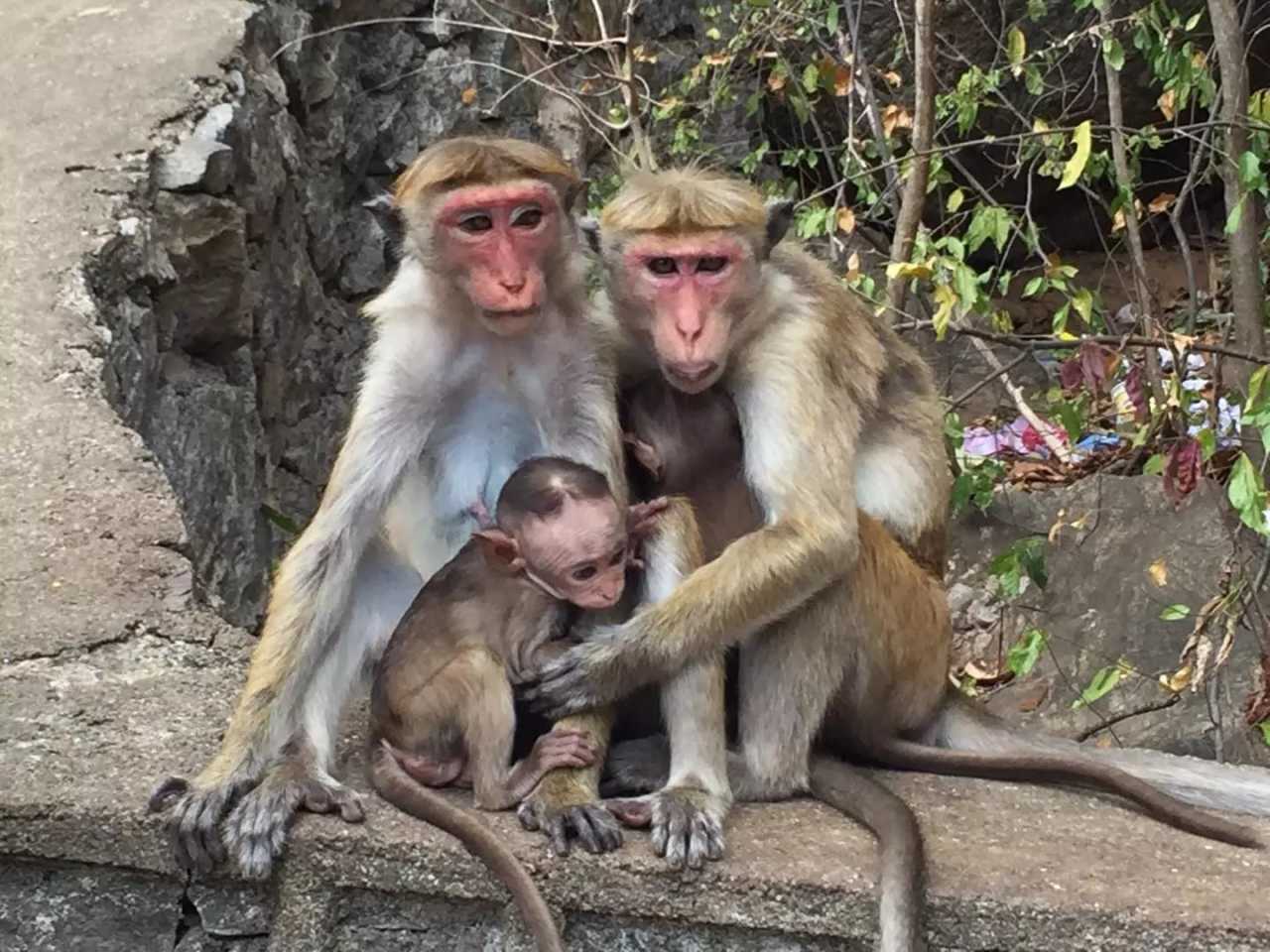

Next we visited Minneriya National Park (90 km²). The great reservoir built by a 3rd‑century king exposes grasslands in the dry season, drawing macaques, sambar, Sri Lankan leopards, and flocks of birds like little cormorants and painted storks. Elephant herds migrate here from Matale, Polonnaruwa, and Trincomalee—wildlife heaven. We entered by open‑top jeeps, six per vehicle, bouncing toward the lake. Through forest we reached a vast savanna; the lakeshore was black with hundreds of wild elephants, feeding, bathing, and playing. Our luck was incredible—to see so many. Jeeps circled the lake, waterbirds gathered everywhere. We stopped within about 100 meters of a group of roughly fifty elephants—calm despite a few jeeps nearby. Parents guarded their adorable calves who nuzzled and played. I was fascinated by how they fed: kicking clumps loose with a forefoot, curling trunks to bundle grass, then lifting it to the mouth. Forest, grass, water, and sky—this whole place is their world. It was my first time so close to wild elephants; we shot lots of photos before reluctantly leaving. That night we stayed in a tented camp, with ample space between tents and excellent facilities—sit at the doorway and enjoy the view.

Tuesday, Sept 13: we drove to the Sacred City of Kandy, stopping at a spice garden where staff demonstrated extracts from about 30 plants and their uses. First major site: the Temple of the Tooth (Sri Dalada Maligawa), Sri Lanka’s most revered Buddhist temple on the lakeshore, famous for housing the tooth relic of the Buddha. Begun in the 15th century and expanded by successive kings, it is grand. The main entrance is the west gate and a moat encircles the temple; halls include the shrine room, drum hall, long hall, chanting hall, treasury, and inner shrine, with the tooth relic enshrined upstairs. In the center stands a radiant seated Buddha; the relic itself is kept inside a seven‑tiered golden casket—each tier nested within the next—capped with a diamond. Three times daily, to the thunder of drums, three senior monks unlock the doors with different keys to conduct puja, after which the outer doors open for devotees to file past the casket. Around the complex stand four devales dedicated to protective deities: Natha, Vishnu, Kataragama, and Pattini. Tradition holds that after the Buddha’s cremation, four teeth remained—one in heaven, one in the naga realm, one in Kalinga, and one in Ujjain. The Kalinga tooth was brought to Anuradhapura in 311 CE, later moved many times amid invasions, and finally enshrined in Kandy. Entry requires security checks; visitors must remove shoes and wear clothing covering shoulders and knees. Ceilings are richly painted and gilded.

Kandy Lake lies in the heart of the sacred city. It was dug from paddy fields to form a large artificial lake and is one of the city’s best‑known sights—like West Lake is to Hangzhou. Tropical trees and flowers line the shore, forming cool natural arcades. A level road encircles the water, and the Temple of the Tooth stands beside it. Lake and temple reflect one another to create Kandy’s most harmonious scene.

In the evening we watched traditional Sri Lankan dance. Sri Lanka, ancient Sinhala—or Ceylon—has a vibrant dance heritage. Kandyan dance is the best‑known form, accompanied by powerful drumming, with flowing hand gestures and spinning movements. The main traditions are Kandyan (highland), Low Country, and Sabaragamuwa. Many performances derive from the Kohomba Kankariya ritual; Kandyan culture’s music, song, and dance are closely linked to it. The classical repertoire includes the 18 Vannam—poetic‑musical pieces created in the 18th century under King Sri Rajadhi Rajasinha—each with fixed rhythms and choreographic sequences, often imitating animals such as eagle, monkey, horse, butterfly, rabbit, elephant, snake, and peacock. There are also martial drills, somersault dances showcasing male prowess, and devotional offerings.

Wednesday, Sept 14 (overcast): we left at 07:30 for the southern coast, stopping at a tea factory to see processing, taste, and buy tea. “Ceylon tea” is the collective name for black teas produced in Sri Lanka, once called Ceylon. Major regions include Uva, Uda Pussellawa, Nuwara Eliya, Ruhuna, Kandy, and Dimbula. By elevation, teas are classified as high‑, mid‑, and low‑grown. Uva is the most famous, alongside China’s Keemun and India’s Assam and Darjeeling—together the four great black teas. Uva yields a robust, full‑bodied liquor fit for milk tea; Nuwara Eliya’s high‑grown teas are light and floral, best taken neat; Kandy’s mid‑elevation teas balance aroma and body and pair well with milk. Sri Lankan tea is low in sodium—ideal for people restricting salt. Via Britain and Hong Kong, Ceylon tea became the base of local “silk‑stocking” milk tea and “yuan‑yang.” High‑grown broken grades brew reddish to bright orange liquors; fine Uva shows a golden ring on the surface; Dimbula is bright red and mellow; Nuwara Eliya is paler, with delicate fragrance nearing green tea. We like Hong Kong‑style milk tea and lemon tea, so we bought some—delicious.

After a further four‑hour drive we reached the Dutch‑period fortress—Galle Fort, the Old Town of Galle, on the southwest coast about 100 km south of Colombo on the Indian Ocean. Built on a rocky peninsula forming a natural harbor with entrances complicated by coral reefs, Galle showcases the interplay between 17th–19th‑century European architecture and South Asian traditions. The fort was first established by the Portuguese in the 16th century, greatly expanded by the Dutch after 1625, and later administered by the British from 1796 to independence in 1948. The inner ramparts run about 3 km; the street grid dates to a Dutch plan of 1669. Fourteen bastions and a drawbridge once protected the north end; houses, arsenals, powder magazines, and warehouses were carefully sited within the walls, with polished stone façades and gates that still lend serenity to today’s streets. The whole citadel hugs the sea; every corner affords close views of the ocean. Here seagulls are rare; crows are everywhere, and locals live peacefully alongside them.

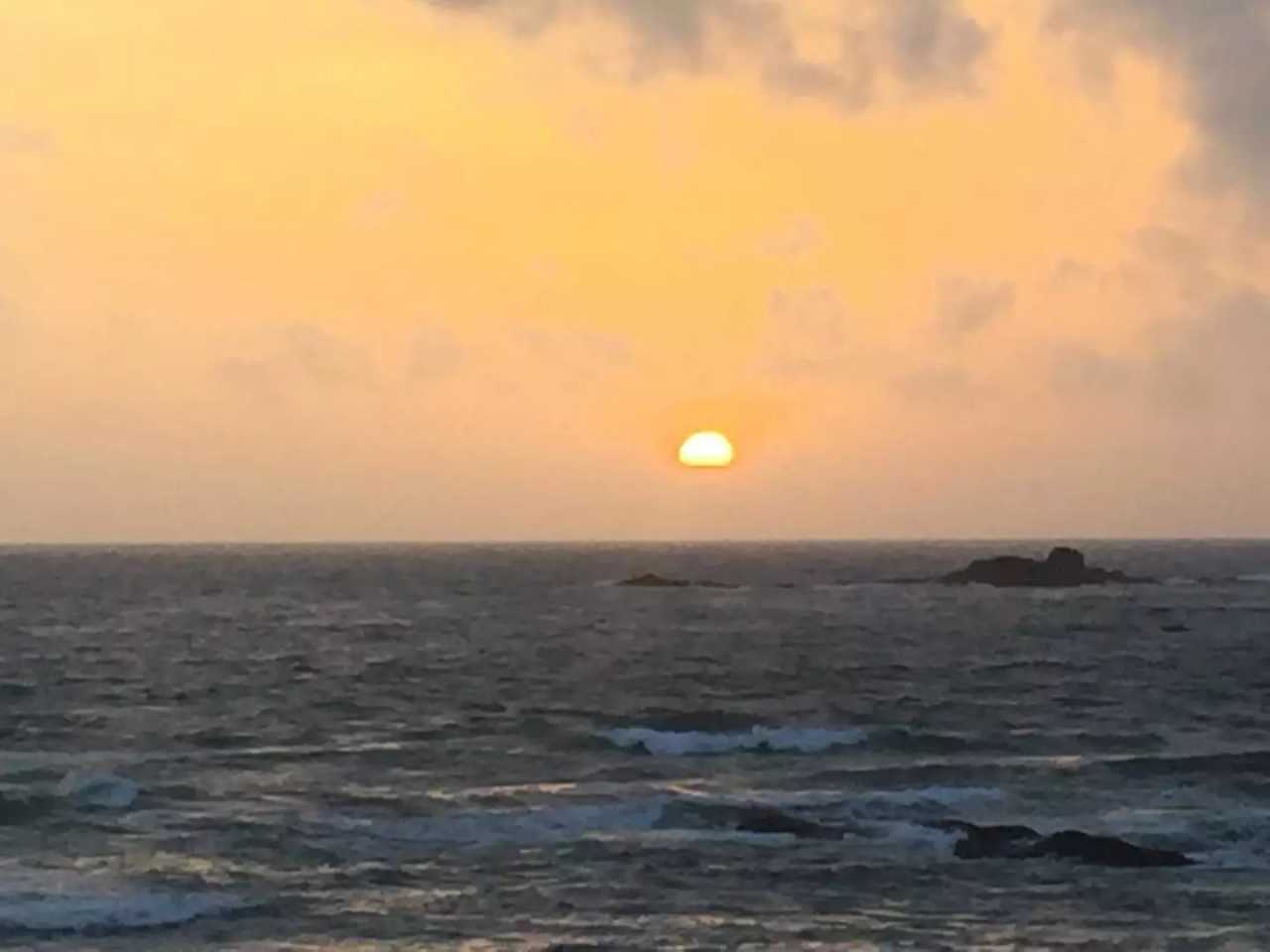

Our last stop today was stilt fishing—the Internet’s most iconic Sri Lanka photo. Though the technique looks ancient, it’s only about 70 years old, born during World War II when food shortages and too many fishermen pushed people to fish in the shallows for sardines. They first stood on shipwrecks, later built stakes on reef. The most famous spots stretch from Koggala to Weligama. It’s striking in pictures, but what we saw was staged: the crew paid fishermen to climb the poles and pose, sitting on narrow crosspieces and casting without bait. For photography, posed scenes are easier than capturing reality, but they lose some of the charm of authentic labor. The Indian Ocean here feels quieter and more demure than the Pacific or Atlantic.

Thursday, Sept 15: we toured a mangrove forest. Mangroves are evergreen woody communities of shrubs or trees that thrive in tropical and subtropical intertidal zones. Special adaptations include buttress and prop roots to resist waves, and pneumatophores—finger‑like aerial roots—for breathing at low tide; many species show vivipary, with embryos sprouting on the mother plant before dropping and rooting in the mud. Some species excrete salt through leaf glands, leaving white crystals after drying; others have thick, fleshy leaves to tolerate saline water. Leaf thickness varies with tidal position. Around the tropical world mangroves have similar forms because they are shaped by saline coastal soils. We crossed the mangroves and visited a small village with many coconut‑made handicrafts; I even saw a porcupine—bristling spines, like a giant hedgehog with a piggy face.

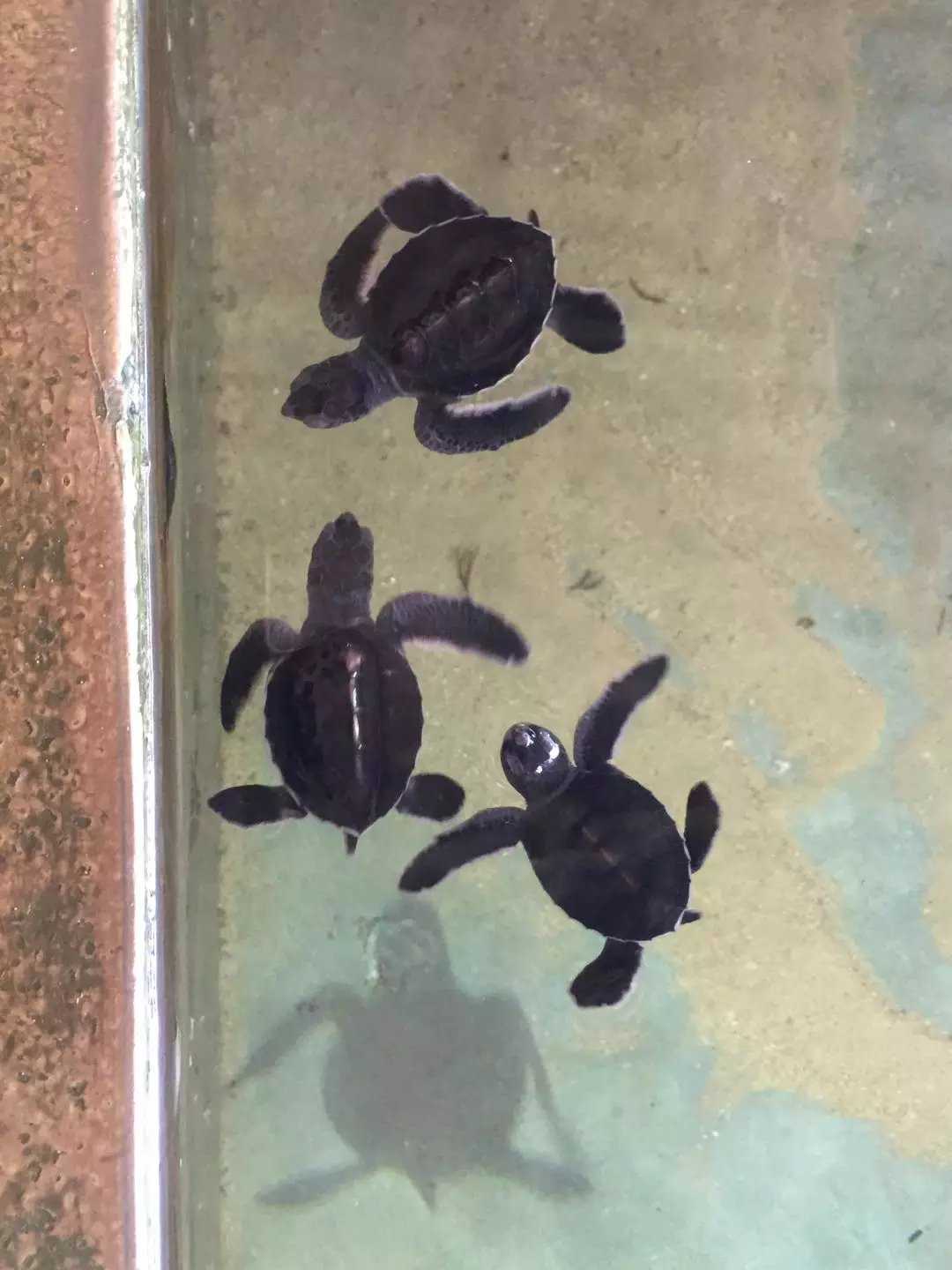

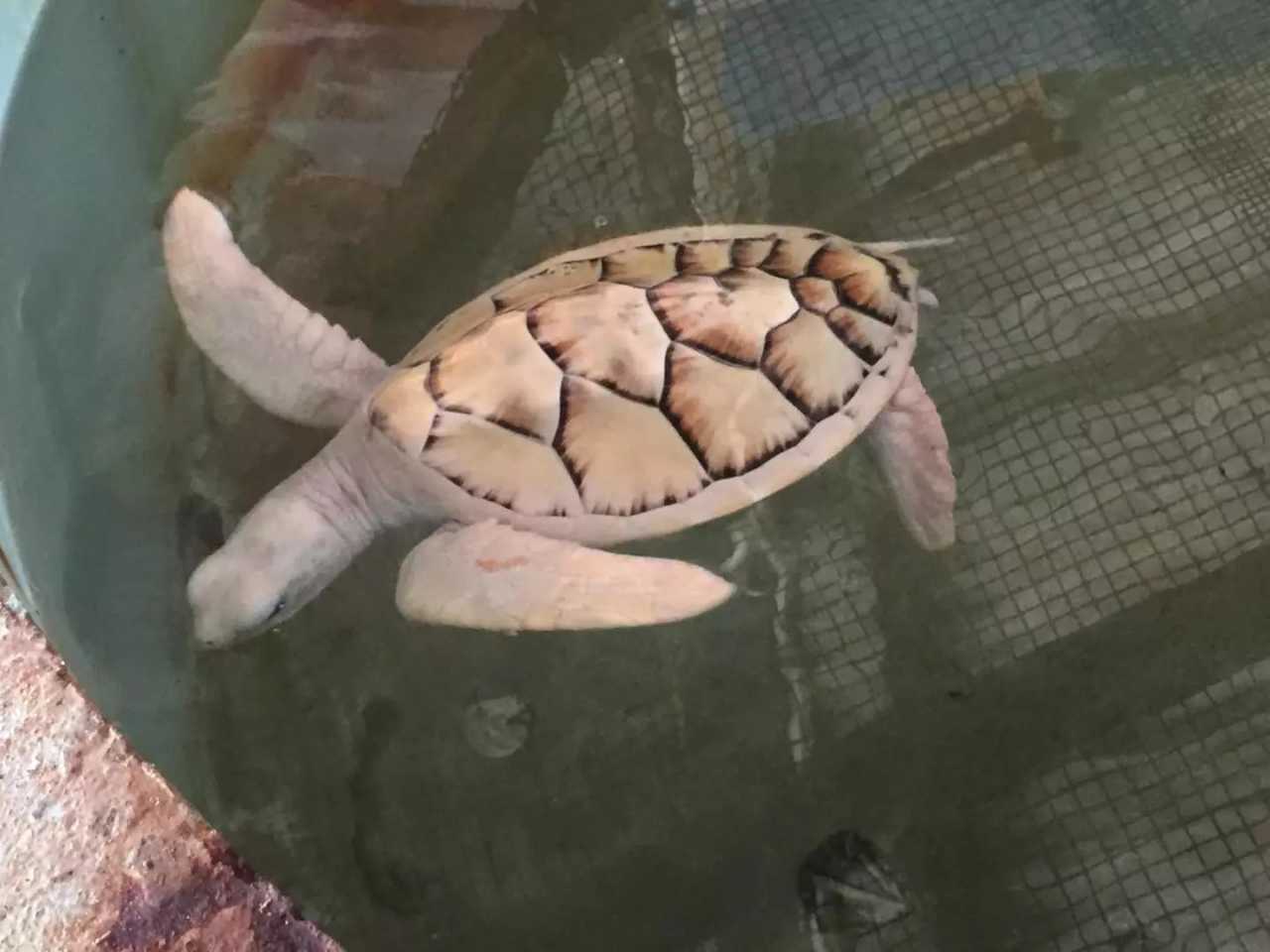

Next we visited a sea turtle hatchery and conservation center. Sea turtles are cold‑blooded; when I held a hatchling its energy was palpable—four flippers wiggling non‑stop. The center looks simple but provides a safe haven for injured or elderly turtles. During hatching season hundreds of babies swim back and forth in the tanks. Staff explained that the tanks are arranged for 1‑, 2‑, and 3‑day‑old hatchlings to acclimate to seawater and practice swimming, so their fragile shells can withstand the ocean; many staff are volunteers.

For lunch we feasted on seafood. After a rest we returned to the hotel’s private beach with fine, clean sand. Sri Lanka is truly a place for leisurely vacations; many hotels let you enjoy the Indian Ocean without even leaving the grounds. It happened to be the Mid‑Autumn Festival—everywhere the moon is equally round. We spent our last night by the sea and the pool, admiring the moon and savoring Sri Lanka.

Friday, Sept 16: the day’s highlight—the famed coastal train. Many say a trip to Sri Lanka must include a ride on the seaside railway, said to have inspired the ocean train in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away. Tracks run just steps from the surf and the Indian Ocean scenery is gorgeous. The line dates to the British colonial era when it carried tea; today it’s still a commuter workhorse. After an hour by road we caught the train to Colombo for a one‑hour ride along the sea. Honestly, the photos online oversell it: the views are beautiful, but on Friday the train was packed—no chance of a window seat, even standing was hard. The cars are old and unair‑conditioned, and vendors weave through the aisles with goods; locals take it in stride. Still, leaning out of open windows with the ocean racing by is a rare experience. Colombo Fort station, in the city center, opened in 1908. It has 10 platforms and handles around 200,000 passengers daily. Compared with China’s big hubs it’s modest, but the network reaches many villages, is affordable, and serves people well.

Leaving the station, we browsed a local mall while waiting for our evening flight.

Our flight departed at 18:35; we arrived in Kunming at 01:58 on the 17th (phones switched automatically from Sri Lanka time to Beijing time at 11:30). Sri Lanka—goodbye!