Last semester, I participated in a workshop on speed reading. The teacher taught us many methods and conducted various training sessions. After the class, I originally intended to share what I learned with everyone right away. However, I also felt that some of the methods were effective in theory but I wasn't sure about their actual results. Some of them worked well in the classroom for a short period of time, but I wasn't sure if they were suitable for long-term reading.

The ADHD brain that runs wild and frantically causes me to read hundreds of pages in a day when I'm in a good mood, but when I'm in a bad mood, I get stuck on books that are hard to read and make no progress for a week. And the books that make me feel bad are not necessarily really difficult to read; it's just that those few pages are when I'm in a bad mood, repeatedly reading, unable to get into the book, staring at the book for hours in front of it, closing the book, and then picking it up again the next time to repeat the cycle.

The state of one's reading ability is not a big deal for ordinary readers. However, if one is in the process of writing a thesis, preparing for an exam, pursuing an academic career, or has a strong desire for self-improvement, then it becomes important. A stable, regular reading pattern that allows for some progress even when the reading state is not optimal. So I decided to use myself as an experimental field and apply these methods for a whole semester. I'll see which ones truly work after several months of testing.

Sure enough, time can prove, disprove, filter and eliminate. Eight months later, I returned to this topic with three golden rules to solve two major reading problems for everyone:

1. When in a bad mood, it's hard to get into the reading. The words float before your eyes, your eyes scan page after page of text, but nothing sticks in your mind.

2. While reading, one suddenly gains profound understanding and inspiration bursts forth in an instant. But once you turn the page, you can no longer find those flashes of inspiration. After a month of not reading, all the content from that period has been completely forgotten.

In the first chapter, if one's imagination wanders off, it indicates that the reading speed is not fast enough.

This point has been the most enlightening for me. The people who joined the speed-reading class came from various professional backgrounds, but coincidentally, most of them were troubled by distractions. The most frequently asked question by the teacher was that when reading a sentence, a thousand thoughts would pop up in my mind. Some were related to the content being read, while others were completely irrelevant. However, they would invade my mind and I couldn't control them to keep them out.

In this situation, the teacher said this seemingly ordinary and even unreasonable sentence. But precisely this sentence made me view my reading problems from a completely new perspective.

Let's think about those moments when we are stuck by a difficult book. We often experience this: unconsciously lose concentration, thoughts swirling around → suddenly realizing our current state and deciding to adjust → starting from the paragraph where we lost focus, re-reading it carefully, trying to make the content "sink into our minds" → and unconsciously losing concentration again.

That is to say, when we realize we have lost focus, our subconscious reaction is to re-read, read carefully, and read slowly, in an attempt to get these words into our minds. However, our minds are already filled with chaotic thoughts, so we temporarily clear our minds and want our brains to devote all their energy to reading. But before we can read even two sentences, the temporarily erased thoughts creep back like vines, swallowing the new task that just came in and taking over our minds until we notice it again next time.

But in this case, we do the opposite. Instead of trying to clear our minds first, and instead of fighting against the vines in our minds, we simply set ourselves a single task. Start reading quickly, as fast as possible. Don't care if the words actually enter our minds or not. Just do pure fast reading. With eyes moving quickly, greedily, aggressively, row by row, in a row you go, without needing several pages. You will find that the words suddenly start to enter our minds, and the chaotic thoughts disappear.

Why?

When in a good reading state, the brain is active but also somewhat relaxed. The purpose of reading is to find useful information for oneself. It might become the argument of your thesis, might provide you with new knowledge, or might offer you a subtle and ingenious argument. The multi-tasking nature of such a state means that we need to absorb and understand new knowledge while constantly making connections, comparing the existing information with our goals, and relating it to our existing knowledge base. Good reading in such a state also involves association and divergence. We compare it to a fluffy yet sturdy sponge of vitality.

However, when the brain is already filled with a chaotic mixture of mixed thoughts, trying to return to a good state for the brain is like having a battle between a sponge and a vine. It's too difficult. It's better to put the sponge back to make a hamburger and leave the matter to a more powerful entity.

At this point, rapid reading becomes a clear and powerful directive that is highly relevant to our task. It is like a tree, taking root and growing, pushing out all the vines. If there are still vines remaining on your tree, it indicates that you are not reading fast enough. You have not engaged the entire brain to perform this single task.

Read quickly, as fast as possible. So fast that the brain is unable and has no time to think about anything else. This is equivalent to giving the weakly centralized brains of people with ADHD or those with ADHD-like characteristics a simple, clear, achievable and task-related instruction.

At this point, perhaps some smart readers will ask: Then how can we read quickly? Well, if I can't read fast, what should I do?

Good question! See you in Chapter 2!

What should I do with the pages I skipped while speed-reading? I always feel bad because I don't think I "read properly".

First of all, the amount of information on these few pages is insignificant compared to the entire book. It is also insignificant for your reading volume over a lifetime, a year, or even a month. It is better to quickly read through these few pages rather than getting stuck on them.

Secondly, trust your brain. When encountering relevant information, your brain will naturally give you feedback. The content that you haven't really absorbed probably isn't that important for you anyway.

After letting go of the mental burdens, then we come to the second part, the section on speed improvement techniques.

Chapter 2: Man-made Auxiliary Lines

The instructor of the speed reading class led us to conduct a rather interesting small experiment. Working in pairs, facing each other, one person would draw circles with their eyes (in an empty manner), while the other person would observe the movement trajectory of that person's eyes. In the second round, the observer would draw circles in the air with their fingers, and the other person's eyes would follow the movement of the observer's fingers, while the observer simultaneously observed the eye movement trajectory of the moving eye person.

(A simple little experiment. Highly recommended that you try it with your friends.)

In such a small experiment, we can clearly observe that when the moving eye is not guided by the observer's finger and merely draws circles with the eyes randomly, the movement trajectory of the eyes is in steps. However, when there is a finger drawing circles in the air guiding it, the eyes and the finger move synchronously. Even if the speed is increased several times, they can keep up and the movement trajectory is very smooth without any pauses.

When we read, our eyes also move in a similar way. When there are no guiding lines, our eyes will unconsciously pause and even jump back to the previously read content, and sometimes even skip words or characters in sequence. Naturally, such sluggish eye movements are difficult to speed up. The repeated unconscious re-reading caused by jumping back leads to a situation where it is impossible to speed up significantly, at least not to the extent that the brain has no time to daydream. Even if only a few words are re-read each time, it still leads to the inability to speed up significantly.

So, how do we construct the guide lines?

The simplest way is a regular card (as shown in the picture below)

Do not have any patterns or words on the cards to prevent them from becoming new distractions. When you reach a certain line, place the card below that line. Continuously speed up the process of pulling down the cards, consciously forcing yourself to solve one line faster.

Similar to the paper card is this reading card with a window in the middle (as shown in the picture below)

The advantage is that it highlights the reading lines more clearly. The disadvantage is that for some people, the upper part is blocked and they always feel uncomfortable. You can decide which type of card to use according to your personal needs and preferences. Functionally, there is not much difference.

The second type of guiding line is drawn using the tip of the pen or the fingertip.

Perhaps many people, like me, were warned by our teachers in primary school not to point at words while reading, as it would make the reading process too slow. Thus, they believed that using the fingers for assistance would be a method that would slow down the reading speed.

But the finger-tip assistance method we are talking about here means placing the fingertip below the line of text being read, then moving it rapidly without any pauses. The eyes should follow the horizontal line drawn by the fingertip and quickly scan the text, similar to directly applying the experiment described at the beginning of this chapter to reading. As for whether to use the fingertip or the pen tip, there is not much difference. It depends on personal preference.

Here we can summarize how to quickly enter the reading state: First, let go of any mental constraints and focus your entire mind on reading quickly. The faster, the better. Secondly, if you find that speed reading is difficult, you can use the method of auxiliary lines to help yourself speed up.

The problems in the first stage have been solved. We have successfully entered a good reading state and our creativity has been sparked. So, how can we ensure that these inspirations are recorded, so that we can find them later and record them without disrupting our current good reading state?

This is the issue that we will be discussing in Chapter Three.

Chapter 3: Building an External Brain.

The poster claims to have a relatively good memory, but it's impossible for him to remember all the books he has read. And it's quite amazing that the more brilliant insights that suddenly come to mind at the time, the faster they fade away. Even if he re-read the original text two months later, it would be so unfamiliar that it wouldn't seem like something he wrote at all.

If it's just for entertainment, there's no need to learn the reading methods. The readers of this article are mostly engaged in task-oriented reading. Therefore, merely reading is not enough. Something needs to be left behind for future use. The inspiration during reading needs to be uniformly stored for easy retrieval.

Some might say that just reading and memorizing at the same time would be fine, so there's nothing more to say. No, no! It was precisely at this stage that I spent the most time on fine-tuning.

My initial reading pattern was to hold the book in my left hand and the notebook in my right hand. Whenever I came across an excellent argument, I would summarize it immediately. Whenever a new inspiration occurred, I would record it. But soon I encountered the first problem: After writing down a great inspiration each time, I would put down my pen, lie down on the bed, and start playing with my phone for two or three hours. It took me a long time to realize the existence of this phenomenon and start analyzing it.

In fact, it's quite easy to understand. When in a good state, the reading goal is clear and the brain's association is effective. So naturally, interesting inspirations will emerge after reading for a while. However, the immediate summary will bring me a pleasant sense of completion. Finding the inspiration (achieving the goal), completing the record (visualizing the achievement of the goal), this entire process is too complete. So the brain directly enters the self-rewarding stage.

Although in reality my original plan was to read xx hours of books and xx pages of books, this task has not even been completed yet.

So we need to postpone the parts that give people a sense of "completion", to prevent the brain from prematurely rewarding itself.

I'm not saying that we shouldn't record our inspirations while reading. The inspirations during reading are fleeting and we must capture them immediately and write them down. I'm merely suggesting that the reading process and the note-keeping process should be separated. Don't prepare a notebook separately while reading. Just write and draw directly on the book. Mark down the key points as you read. When you have an inspiration, write it directly on the blank space of that page. After reading all the content, then organize these pieces of information into your storage system. The storage system can be an electronic document or a physical notebook, depending on your personal preference. (This is actually a variant application of the method I previously wrote about preventing distractions from mobile phones.)

See: A Small Method to Reduce the Chance of Being Distracted by Mobile Phones

Reading and organizing can make our tasks clearer and help us receive more feedback. We need to prevent our brain from self-rewarding prematurely when it shouldn't do so, but at the same time, we should also give it enough rewards and not squeeze it too hard. If we read and organize simultaneously, we can eliminate the frequent unavoidable times when we go back to the bed to play with our phones. The overall process is 12 hours, with reading and organizing intertwined throughout this period. But solving one book, this most obvious achievement, requires 12 hours to achieve. However, if we focus on reading first and then organize later, it takes 8 hours to finish reading and 4 hours to complete the note-taking organization. The task is clearly divided into two segments, and with shorter time, we can experience that a book has been finished. There is a small positive feedback at some point during the process, and organizing the notes then forms a new task with a new sense of achievement. Separating the process is equivalent to objectively shortening the process of "finishing a book", preventing the brain from getting into a negative state when it realizes the process is too long and the progress is slow.

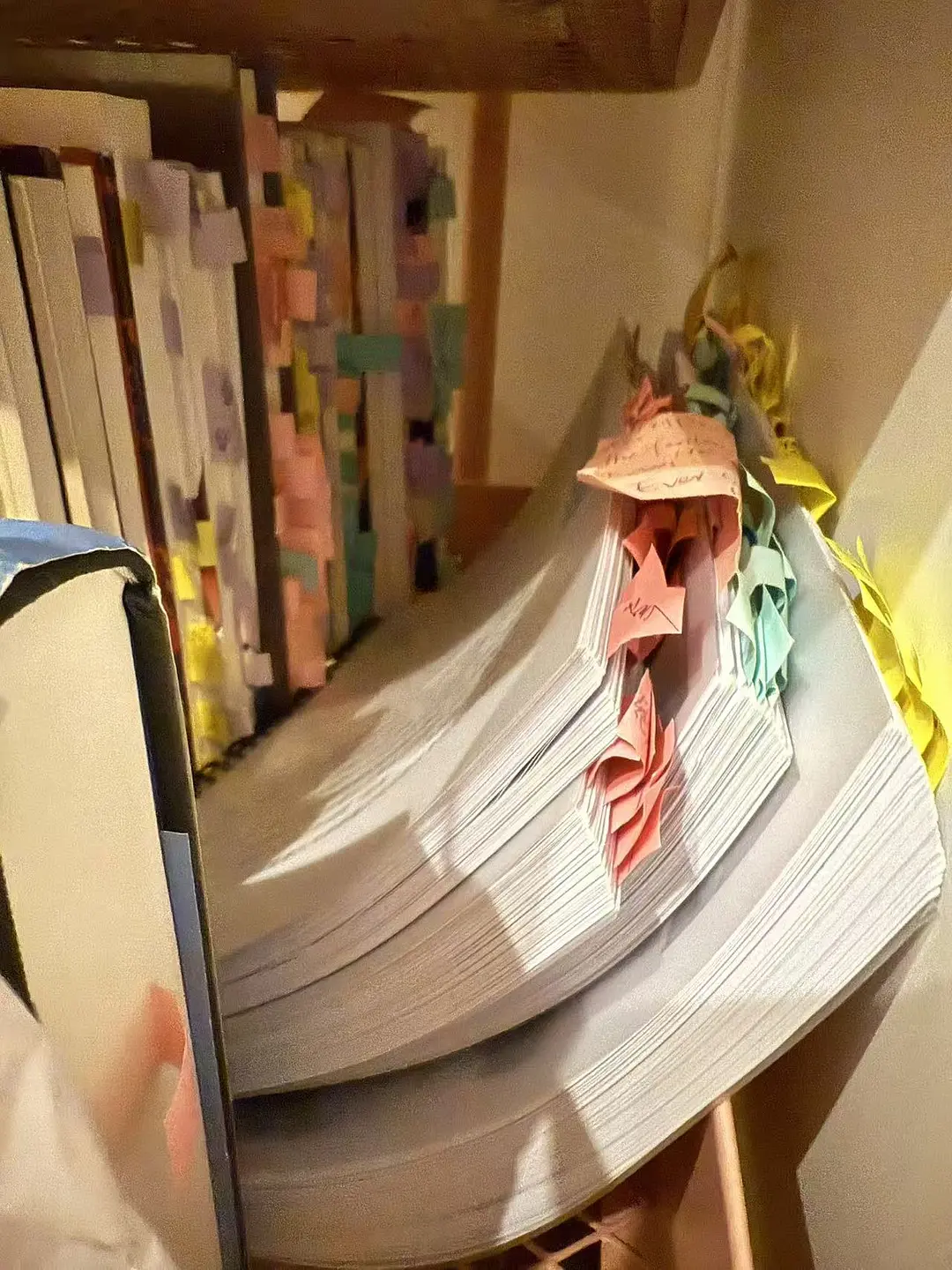

The introduction of sticky notes serves two purposes. Firstly, it prevents us from ever being unable to locate these key segments on the page, and also makes it easier to locate them when we need to organize our notes. Secondly, sticky notes have dual attributes. They provide a simple and limited sense of satisfaction, and also mark the emergence of new tasks that have not yet been completed. As we read, the number of sticky notes increases, and the parts we have read become more visual. This partially meets our brain's need for feedback. However, on the other hand, since our system uses sticky notes to mark the information that needs to be organized, after reading, we still need to go through the emphasized content on the sticky notes to reemphasize the points that need to be addressed. Therefore, the increase in the number of sticky notes also reminds us that there are still these tasks that need to be resolved, preventing our brain from directly entering the completed state after finishing writing.

Details of the Incident Report Card:

For me, the three main types of information that I need to summarize and retain after reading are: the book and movie recommendations I made, the paragraphs that trigger my imagination or are useful for future reference, and the information that requires further verification.

At first, I tried to distinguish different types of information by using different colors. But soon I realized that this would impose an extra burden on me. Every time I needed to attach a memo card, my mind had to think about which color corresponded to which information. The process of choosing the color of the memo card was enough to disrupt my train of thought. Moreover, it was easy to forget to bring enough memo cards of different colors when going out for study. So I quickly simplified the process by using single-color memo cards instead of different-colored ones, but I would mark simple, convenient and fixed symbols on them.

The design of the symbol system must be simple and easy to use, with everything being clearly visible without requiring any additional memorization. Personally, for a rough list, just draw a rough symbol. For ordinary inspirations, no additional annotations are needed. For important inspirations, put a star next to them. For information that needs to be confirmed again, draw a question mark.

Finally, after organizing, the steps of preparing the report cards are as follows: the draft list and the information that needs to be confirmed form one group, and the ideas for organization form another group. They can be separated and processed separately. After marking the necessary papers and books for the movies in the draft list, the report card with the "draft" written on it can be directly pulled down. Once the confirmation information is confirmed, the report card with the question mark can also be pulled down. Let only the reminder highlights and the ideas on the report cards remain at the end of the books. Even after the final organization is completed, they can still be kept for easy review and refreshing.

The information organization process might take longer than expected. Maybe it took 8 hours to read a book, but it took 4 hours to organize the information. There might be such an unprofitable perception, but believe me, this information storage system is actually the most efficient in the long run. It's like condensing every 200-300 pages of a book into 3-4 pages of notes that are highly relevant to your needs and your theoretical framework. When you really need to use it, flipping through your own hundreds of pages of notes will definitely be much more efficient than reading tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of pages of books.

When organizing, be sure to pay attention to marking on the header of each page of the notes which book the content comes from. Whether you copy the original text or not is fine, but remember to mark the page numbers. During the organization process, just make a brief note on each page. This can prevent you from having to search through several days looking for the page numbers when you need them later.

To sum up briefly: When the brain is unable to enter a state, use the fastest and most effective speed mode to assist it in entering a good state. If it is difficult to increase the speed, then the auxiliary line method can be introduced.

When in a good reading state, adopt a process of separating reading from note-taking, which helps prevent the good state from being interrupted and shortens the book-reading process. To facilitate the subsequent organization, use single-color post-it notes during reading, supplemented by a simple and fixed symbol system for identification. After finishing the book, force yourself to spend time organizing the notes for future use.

So, if one's current condition is so bad that there's simply nothing that can be done about it, what would be the solution?

Let go of yourself, have a good sleep for a while, and then read two simple and enjoyable books that you usually love, such as mystery novels, horror novels, Jane Austen's works, or anything that can make you feel as warm and familiar as a soft blanket.

When describing the system I am currently using, I spent a lot of words elaborating on the reasons, comparing the system's functions with my requirements to determine their compatibility. This was done to present a set of the system's principles to everyone. If people with the same requirements could directly use this system, it would be great. However, I also hope that even those who cannot directly use this system can be inspired by the principles and experiment to create a system that suits them better.

I hope everyone can regain the joy they felt in their childhood when they were so engrossed in reading books that they thought they could keep reading like this forever.